Interview with Michael Robinson

By Cat Tyc

And We All Shine On / Michael Robinson

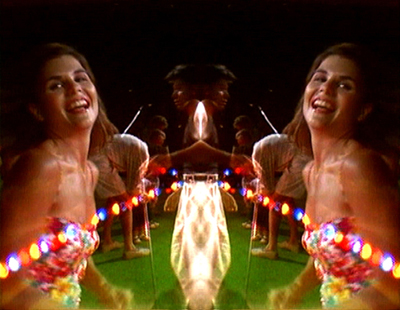

The first time I saw Michael Robinson’s Light is Waiting (2007) – a visceral dismantling of the Full House Hawaii hijinks episode – I had a revelatory “flashback”: With his controlled but blatant overuse of the video “mirror” effect, Robinson exposes the horror that lays beneath the surface of 1980s television but somehow makes it psychedelic and deep, less something to be ashamed of and more an explanation of who we are and how we came to be, warts and all.

There is a traditional quality to Robinson’s work, which is informed by and respectful of experimental cinema trajectories (especially the Structural Film strain), but at the same time, it’s also very contemporary, very “now.” Maybe it’s partially his appropriation of television shows from the 80s and his unabashed use of pop music, but what excites me most is the confidence he has to dance with accessibility and to balance that almost effortlessly with artistic ingenuity and integrity.

After attending a screening of Robinson’s films at the Cinema Project in Portland, Oregon in 2007, I wanted to know more about his work. The ensuing conversation took place over email, prompted by my curiosity over a piece of music in his recent film, Victory Over the Sun (2007).

* * *

CT: Before we talk about anything else, I have to know: Is the score in Victory Over the Sun “November Rain” by Guns N’ Roses?

MR: Yes, it is “November Rain,” played by the Vitamin String Quartet.

CT: The first time you picked up a camera (Bolex or video) what did you shoot, and where were you?

MR: My sister and I made a lot of videos together when I was about 10, most of which were remakes of movies we liked, or interviews with celebrities (like the cast of Little House On The Prairie), and often involved me wearing a wig and a nightgown. Our remake of Poltergeist [Carol Anne is Dead, 2008] is particularly good.

CT: Something that strikes me about your work is the original way you appropriate material. A perfect example would be the sequence in And We All Shine On (2006) where you marry P.O.V. video game images of people searching cover a sparse landscape to the karaoke version of Sinead O'Connor's “Nothing Compares To You” cover. Can you share a little about your process of matching images to sound. Is it a trial and error process or do you have a particular element (like the sound in mind) and find yourself searching for the right image, or the other way around?

MR: When I’m shooting and gathering materials, I generally let myself work in a pretty intuitive manner, trusting that I’ll make sense of things in the editing. In that respect, I do usually begin with a few different types of visual material, and the sound works itself into the process as the relationship between the different types of imagery starts to take shape. Sound has become increasingly important to my work, and in a lot of ways is the most important element of several pieces, Victory Over the Sun and The General Returns From One Place to Another (2006) in particular. I tend to think of my films as narratives created though non-narrative materials, and I think sound has become the outlet for me to steer that narrative, setting the tone and controlling the emotional and psychological affect of otherwise open-ended materials.

CT: During the introduction to your Cinema Project screening in Portland, you mentioned that there was a certain theme in the trajectory of the pieces you showed that night. I was wondering if you could elaborate on that.

Stills from Light is Waiting / Michael Robinson

MR: Sure. In 2001 and 2002 I made a series of films dealing with the loss of my father, who died of leukemia in 2001. These were emotionally direct, silent, 16mm color films, which incorporated a lot of re-printed home movies and a lot of idealized rural landscape. After making this series and having some time to step back from them, I was unsure of what to make of the whole experience; the films had been an integral part of my grieving process, but this meant that part of my personal life was forever bound to strips of celluloid. I was less turned off by the personal nature of the films than by the ease at which 16mm film seemed to capture and portray loss. In short, I eventually became interested in subverting the same engagements with nostalgia and beauty I had unassumingly conjured in these earlier works, making work which references these conditions without being entirely of them–as a way of questioning the very nature(s) of romanticization, seduction, manipulation, etc. 16mm film is a dangerously beautiful medium, and it’s quite easy to make a ton of really pretty drivel with it (which is not to say I think my earlier films are drivel–but something needed to change).

CT: Something I noticed was how you seemed to have many images of nature (in the woods, trees, bushes) and I was curious about that. Is being in nature something you particularly enjoy, or was it just that you had a certain proximity to it when you were in Ithaca? Or something else?

MR: I am a sucker for landscape in general, but I think its inclusion in my films is a little more complicated than that. In college I was exposed to a large amount of landscape-centric experimental filmmaking, from both lyrical and structural traditions, and really fell in love with it. And so in a lot of ways, I feel my use of landscape references that history, not in any mocking way, but as a means to conjure up an established cinematic language as a platform from which to push off from. I'm also really interested in the uses of landscape in a lot of narrative filmmaking (particularly science fiction and horror), and in Romanticism’s regarding of the natural world as the site of spiritual exchange and transformation. So it’s a mix of things.

CT: What is the direction that your work is taking currently?

MR: I’m actually about to throw myself into editing a new piece I’ve been shooting very slowly over the past year or so. I never really know how something will turn out until the very end, so I’m hesitant to try to pin it down now too neatly at this point. But in my head, this film is hovering around some ideas of purgatory, boredom, incest, television and transcendence, though it might decide to be about something else as it takes shape. The film follows three “contestants,” each stranded in a different landscape and engaged in a kind of survival ritual. They find each other in the end, sort of.

Published January 1, 2010

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cat Tyc is a video artist/filmmaker whose work has shown at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Camac d’Art in Paris, High Energy Constructs in Los Angeles, and the PDX Fest in Portland, Oregon. She currently lives in New York.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Counter-Archive