Jon Rafman

In conversation with Walter Forsberg, and Jieun An, Seth Anderson, Caitlin Hammer, Rufus de Rham, Marie Lascu, Taylor McBride, Bono Olgado & Crystal Sanchez (graduate students in New York University’s Moving Image Archiving & Preservation department).

Taken from 9-Eyes (Jon Rafman) / Courtesy of the artist and Google

Taken from 9-Eyes (Jon Rafman) / Courtesy of the artist and Google

On March 21, 2012, NYU’s Cinema Studies Department invited Canadian artist Jon Rafman to give a public lecture about his artwork in screen medias, internet worlds, and machinimatic narratives. Earlier in the day, Rafman sat down with graduate students in NYU’s Moving Image Archiving & Preservation program to discuss preservation strategies, concerns, and anecdotes with regards to his work.

* * *

INCITE: To begin with a question particularly relevant in this media preservation course on ”Handling Complex Media,” I’d like to ask: What do you consider the format boundaries of your work employing the internet to be? What kinds of format platforms do you envision your work inhabiting in the future?

JON RAFMAN: Like that touch-and-grab screen in Minority Report (2002)?

INCITE: Exactly.

JR: Well, working with the Rhizome Art Base has really been the only time, thus far, where I’ve had people help me think about my work in the long term. In thinking about websites, because I sell works to collectors, one issue that arises is the nature of a collector’s ownership, if a website work is available for everybody to view. Ultimately, someone ends up technically owning the website, which means that they own the code: a property that I sell. With the collectors that I’ve been dealing with, longevity (exclusivity or exclusive ownership) hasn’t even really been an issue that they’re thinking about. But, you’re right that this will become more of an issue when a work might be sold to third party down the line.

INCITE: Do you have any examples from your contemporaries, in terms of what “deliverables” for digital works are sold and acquired by art collectors?

JR: Among the digital works that I’ve sold have been websites, and the reason that I like that as a deliverable is because a website is a real property. It’s trackable. For example, you can transfer ownership of a website to someone via Go Daddy. I have spoken with other artists, such as Michael Bell-Smith and Paul Slocum, about this issue. Paul Slocum ran a gallery in Dallas for a while and had to master ways of delivering objects. Usually, it involves providing a huge variety of formats to the purchaser: a hard drive; a Mac Mini that can plug right into a monitor, and instantly execute; then, the highest quality file on a storage unit like a hard drive or DVD for archival purposes; and, maybe a second playable DVD so collectors can easily show their collection. Michael Bell-Smith told me that he would tailor-make a really fancy wood box that housed everything, and then throw in two white gloves—just as a gesture. That’s an instance of a deliverable for, say, a video piece. You want to give over something substantial, so that the collector feels like there is something being bought. Unlike many digital artists, the commercial art world still fetishises the object and gives primacy to it. The artist needs to find a compromise between the ideology of their work and the desires of the collectors and the art market.

INCITE: I’ve seen the DVD casings that Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle (1994-2002) was sold in, and it’s terribly elaborate with all sorts of elaborate painted mouldings. Then, inside the box, is just a plain optical disc.

JR: Packaging. It’s all about the packaging—the frames.

INCITE: Do you feel comfortable giving over the source code for a work? In doing so, aren’t you in a sense giving over the ability to not only make copies of, but changes to, the work? Gary Hill’s insistence on CRT monitors for displaying his work comes to mind, at the opposite end of this spectrum of format mutation.

JR: From my perspective, the more versions of something that exist, the more cultural power the work will have. I like the idea of how many variations of a work that can exist. The concept of the “original” becomes more abstract, and it becomes more about the idea of the work than any particular one piece. You can watch these internet-based works on all types of screens, and each has its own quality to it. Obviously, some have a better look, or more intimate feel, or the sound quality is better. But, it’s not like I feel one has a true experience and another an un-true experience of what the work is.

INCITE: Do you make a hierarchy of intentionality or authenticity, when it comes to preferred displays and versions?

JR: I guess it has more to do with pain thresholds—the same way that a filmmaker can’t always afford to control the conditions in which her movie is screened. It might be on a TV, with the color all wrong, and while showing it to her family she shouts, “This isn’t how it’s supposed to look!” There definitely is a hierarchy in that sense: “This is not how I want it to be experienced.” But, I never let myself get too bogged down by that hierarchy. The reality is that if you try to limit your work to only being viewed in the perfect condition, then it might never be seen.

INCITE: What about 9-Eyes (2009-)? What are the core aspects of that work, particularly with regards to how people experience it? What is the work’s essence—the web interface, the infinite downward scroll of images…?

JR: The essence of the 9-Eyes.com site is the web. But, the essence of 9-Eyes and Google Street View as projects is larger. The website is just one expression, or one jet, pouring out of a fountain.

Taken from 9-Eyes (Jon Rafman) / Courtesy of the artist and Google

Taken from 9-Eyes (Jon Rafman) / Courtesy of the artist and Google

JR: The scrolling experience is crucial to the internet experience of 9-Eyes.com because it is a more immediate one. There’s something intrinsic to the internet about immediate stimulation, and scrolling is very much key to that. I don’t expect people to meditate on a photograph online like you would a large C-print at a museum or gallery. Whether it’s text, video, images, hyperlinks, or whatever, everything on the internet is connected by the act of scrolling.

INCITE: So, you have these different instantiations of 9-Eyes, then: The internet version you scroll through, and the C-prints, which you sell. How do you deal with resolution issues when making those C-prints?

JR: That becomes one of the points where my craft comes in. I’ve become a master of understanding algorithms used to blow lo-res images up. Sometimes, I’ll add artifacts to hide other artifacts. For example, I might add some grain, I’ll do some color correction, and I can touch up the images a little bit in order that they look how I want them to look. In some ways, they’re nostalgia-fied, like an Instagram photo, by my touch. But, I kind of like that aspect of it and I don’t feel that I’m doing any more than a photo-journalist would do to his photos of wartime.

INCITE: So, then, 9-Eyes kind of has at least these two different contexts. If a collecting institution were to purchase the work, would they get a database of the images?

JR: My work can be presented in two formats. Firstly, it can be acquired by an institution or an individual. Each piece is an addition of one, accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. The second format is one that artists do in general. As I did for the Moscow Photobienniale and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome, my work is presented in the form of an exhibition or festival and then they are exhibition or display copies.

[Rafman’s cell ringtone (the funky opening bassline from Seinfeld) briefly interrupts the discussion.]

JR: If I were really concerned, I would insist that the display copies be destroyed after exhibition. I know that [photographer] Edward Burtynsky’s lawyer requires notarized testimony that display prints are destroyed after an exhibition is over. But, Burtynsky sells his photographs for, like, $5 million. In that case, the certificate of authenticity becomes really important, and almost like the artwork itself.

INCITE: I’ve noticed that several other artists working with Google Street View images remove certain Google-y artifacts like the navigation bar and logo. You leave them in. Can you talk more about that?

JR: I truly believe that those are important. I like to see those things as found objects. Making the means of production transparent is one of the most important things an artist can do, and the more of an illusionist you are, the less interested I am in the artwork. Part of modern art is the gesture of pointing to how it was made. This frees the viewer a little bit more. It lays bare what an artwork is, revealing its constructed-ness. When you remove the logo, I feel like it’s lying on a deeper level than when I do actually lie. You can lie, and point towards the constructed-ness of your lie and it’s still truer than works that mask their modes of production. A great example would be a dramatic Hollywood movie about a historical event that totally conceals the fact that much, or all, of its plot is fictive and manufactured. With those Google-y artifacts, you can also see some evolution of the company: how they’ve changed their design, etc. Minutiae, like how they change the look of the compass, or how they change the disclaimer at the bottom (it used to say, ”Report a concern” under every picture, and now it says, ”Report a problem”), however seemingly insignificant, can be revealing over time. It just seems awful to get rid of those things. One of my favorite cultural theorists Walter Benjamin, in the course of his Arcades project, compared what he was doing to couplists who correlate numbers with words in the Bible and extract some esoteric meaning or deep truth from otherwise seemingly insignificant things. That’s why I like including those little details.

INCITE: Do you ever have problems with copyright?

JR: Some people are definitely scared of infringing copyright if they present my work. Copyright law in this area is truly new, so there are grey areas and the law is constantly evolving and often contradictory. As I believe wholeheartedly that my work is truly art and social commentary, and that critique or celebration are core to it, I circulate the work as much as possible (for example, through Tumblr). As I see Google Street View reflecting contemporary experience, my general strategy is to illustrate this by having the Google Street View work become part of the cultural consciousness. The fact that I was to be paired with a Google Vice President at this conference at the New Museum [the 7 on 7 Conference, April 14, 2012], and that major international newspapers and magazines have presented my work, leads me to think I’ve reached the point where I’m somewhat safe. Sometimes, I think it’s certain individuals who get more perturbed than it is the corporations. There can be so much vitriolic anger at people who use appropriation. But, I’m no expert in this domain.

Taken from Kool Aid Man in Second Life / Jon Rafman

INCITE: Copyright issues would seem additionally complex since you’re dealing in virtual worlds.

JR: Right, like the virtual worlds in Second Life. The fact is that I live in this world that is dominated by present copyright laws that do not reflect the nature of digital culture. By widely distributing my work and arguing that my work is consistent with the historical role of art comprising moral and social critique, I feel I am advocating for the formulation of more relevant contemporary copyright laws. I often see myself in an “Artist-As-Amateur-Anthropologist” role.

INCITE: Where you point and say, “Look!”?

JR: Where you point and say, “Look at this furry subculture that eats each other, and has a language and set of protocols they’ve developed for virtually eating each other.” In these virtual worlds there are buttons you can press where you physically enter someone’s stomach to just hang out and look at the inner wall of their belly. It’s all cutesy-wootsy but it’s also extremely sexual. Given that these things exist in virtual worlds, I want to ask: “What does that reflect on the rest of the world?” The line that you have to walk is to not be seen as mocking the culture, by calling attention to it.

Taken from Kool Aid Man in Second Life / Jon Rafman

INCITE: As some kind of self-described amateur anthropologist, then, archivists should look at your work as anthropological instead of solely artistic?

JR: I think that it’s different than, say, if you objectively looked as Google Street View’s entire collected images as a whole. I’ve selected certain images that are important to me, and that I find interesting. If you were to seriously study Google Street View, I would say you would have to take into consideration the interactivity and searching aspects of it.

INCITE: Twinning that experiential context with the aesthetics of the individual images does seem key. What will the significance of your 9-Eyes images be if, in 30 years, people don’t even know what Google Street View was?

JR: That they might wonder what the compass thing is and ask, “What’s this primitive interface?”

INCITE: Right. Like: “What is this compass thing? That doesn’t compute with the brain-implant-webstream-chip-of-consciousness that is the normal experience of everything in my life.”

JR: Cory Arcangel said something really interesting when asked about how his Color Gradients (2008-) will be understood in future decades, saying that it would either age well… or not. As an artist you can never know how something will age. A work could end up being extremely profound, or it could be deemed far too obscure. There’s no real way of knowing. I think this is a question that comes up in every generation of art.

INCITE: While we were getting coffee before class, you mentioned that you are coming to realize how your work is quite archival in nature. I’m wondering how you fell into that kind of documentative trend in your work.

JR: Basically, my practice evolved in that direction. Before I really started surfing the internet I was making movies, and I actually knew of Walter from the filmmaking scene in Canada. I was making montage-y, Chris Marker-style films that dealt with history and memory. I began to get tired of the film world, though, because it was so big and I was having a hard time finding my community.

A lot of Chris Marker’s practice revolves around finding old footage, which I was trying to do, but for the internet age. In the course of searching for images and video I discovered this community of “internet artists,” as they were called at the time, through the social bookmarking site Delicious. A lot of the members of the nastynets.com surf club were also members of Delicious and would find internet ephemera and share it, maybe with a little comment or two. Through that emerged this vibrant new vernacular using the signs and symbols of the internet, made by people with art and art education backgrounds. They were in dialogue with each other online, and shared many of the same sensibilities as myself, using humor and irony. I think that they were so ahead of their time that it doesn’t even seem like a big deal now, because there are so many of these blogs, like Boing Boing or whatever. In this community I really found people with whom I could dialogue, and I often say that it was like me finding my Paris of the 1920s, only on the internet. It was one of those “Oh Wow” moments, and it only happened after I finished doing grad school in 2008, so I was a few years behind in the conversation. That’s when I started the Google Street View project and Kool Aid Man in Second Life (2009-). In a way, I came to see myself as though I were a Pro Surfer just like the members of Nasty Nets.

INCITE: It seems like your artworks influenced by the web are the ones everyone is buzzing about.

JR: I feel like my work and I don’t even need to be connected to the internet all of the time. We live in a post-internet world. No matter if you are a figurative painter drawing nudes, you’re still influenced by the internet.

INCITE: Marshall McLuhan once said the same thing about television.

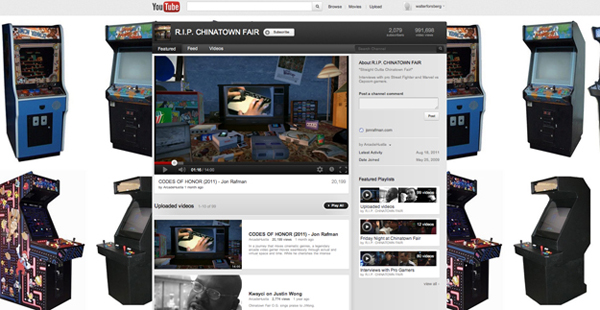

JR: But, I’m not only interested in ephemeral digital worlds. For two years, overlapping with the time that I lived in New York, I would go to this now-defunct arcade in Chinatown called Chinatown Fair.

Taken from the ArcadeHustla YouTube user page / Jon Rafman

Taken from the ArcadeHustla YouTube user page / Jon Rafman

INCITE: Have you heard that it’s recently open, again?

JR: Really?! I did not hear. That’s so exciting! Well, I interviewed all the great gamers that would hang out there for my ArcadeHustla project. Basically I have hundreds of interviews with Pro Gamers, and out of these interviews I created a short film, Codes of Honor (2011). The movie doesn’t really use the interviews, themselves, so much as it integrates the stories that I heard. I just really like the arcade because it’s something that no longer really exists in America. This is really perfect for this graduate course, actually. The interviews got around online and the gaming community ended up using this as a forum to argue for who the best “Ken” [from Street Fighter] was in 1998, or concerns like that. The conversations that emerged in the YouTube comments section were really the great success of this piece.

In a sense, the concept of “time” in the video game world is super-accelerated. Because the games are commercial products, and companies are continually putting out newer versions, there’s no real money in becoming a Pro Gamer except, maybe, in South Korea. So, being a Pro Gamer becomes a thing about honor. Your lifespan as a great gamer is also quite short due to the fact that specific games will only be popular for so long, and also that your hand-eye coordination peaks when you’re in your late-teens. Consequently, there are all of these people who are in their late-20s talking as though they were old minor league baseball catchers in their 50s. Video games are such a big part of culture, yet I don’t think it’s taken seriously in terms of the communities that form, or the more humanist elements involved in being a video gamer. I felt like that was important to document with the ArcadeHustla videos. Nobody outside the gaming community really knows about this piece—I don’t even really know if it’s an artwork. It might be more like an archive of oral histories, something like an Alan Lomax project.

INCITE: They are totally amazing, and something I’ve never seen others do. What about archiving your own work for posterity?

JR: You know, I’m so in the moment right now that I haven’t had the time. I’m just worried about surviving as an artist right now. I think that’s the case as well for a lot of my contemporaries. There might also be somewhat of an inherent taboo to preserving this stuff: growing up and consuming the internet so much, maybe it comes across as narcissistic, in some stupid way.

INCITE: Where would you like to see pressure for archiving your work come from? Galleries? Collecting institutions?

JR: I think it would be great. The more discourse there is about how these complex digital medias can survive, the more of a place they will have in the art market. The top museums and gallerists are beginning to realize this. The videos are a little different, but, like for the JavaScript Sleeping Shepherd Boy (2009) stuff, it’s hard to tell what browsers are going to look like in the future, and even what “browsing” will be. It’s all new ground to break, and it’s all going to happen in practice. But, again, I don’t think that most contemporary artists are even dealing with this. Really, it’s only Cory Arcangel and Ryan Trecartin—digital artists of my generation—who have been allowed into the higher echelons of the art world.

Jon Rafman / Courtesy: Photo Booth

Jon Rafman / Courtesy: Photo Booth

Published June 27, 2012

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Walter Forsberg works as a Research Fellow in media preservation at NYU, and is a contributing editor to INCITE.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Back and Forth