Against the Current: A Two-Part Interview with Karl Lemieux

(and Daïchi Saïto)

By Brett Kashmere

An electric presence on Montreal’s emergent experimental film scene, Karl Lemieux has been composing artistically adventurous time-based media since the late-90s. His first project, a video interpretation of Lee Ranaldo’s talking sound-piece “The Bridge” (1985), made while attending high school in the Nevada desert, foreshadows Lemieux’s recent projector performances with live musicians. Deeply influenced by Québécois animator Pierre Hébert’s interdisciplinary film practice and mirroring his artistic trajectory, Lemieux explored hand-painting in Motion of Light (2004) before embracing the more aleatory possibilities of expanded cinema.

In 2006, Lemieux began an ongoing series of performances with the musician Radwan Moumneh (Jerusalem In My Heart) that brought Lemieux’s cameraless filmmaking techniques into the live arena. Orchestrating an assortment of hand-processed 16mm film loops through a suite of aged Eikis, Lemieux bleaches and paints filmstrips seconds before they hit the gate. Visually manifesting the intensity of Moumneh’s dense, chamber-style guitar, the violently handled and ruined film loops come close to the point of cathartic self-destruction. Lemieux has also collaborated with members of Godspeed You! Black Emperor, A Silver Mt. Zion, Shalabi Effect, Arcade Fire, and Set Fire to Flames, the spoken word artist and poet Alexis O’Hara, and the artist-musicians Alexandre St. Onge and Jonathan Parant.

In addition to his filmmaking initiatives and collaborations, Lemieux is also the co-founder of Double Negative, a collective of Montreal film and video artists dedicated to the production and exhibition of experimental film. Double Negative’s rising community presence, coupled with their advocacy of cinema’s wondrous, transformative potential, has provided Montreal’s independent projection locales with a bolt of positive energy, helping to solidify a ground for future activity.

I interviewed Lemieux at his home in Montreal’s Plateau district in summer 2007. Later we moved up to the Double Negative studio in Mile End, where the collective’s other founding member, Daïchi Saïto joined us.

Lemieux performing with Just’au Crane (Alexandre St-Onge and Jonathan Parant) at

the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT), Montreal / Photo: Nicolas Bilodeau

PART ONE: Personal Work

BK: My first question has to do with collaboration. Do see the projection aspect of your performances working together with the music in a kind of ensemble way, or do you see it (approach it) as something more autonomous. Do you think of the image–the projection–as musical in any way?

KL: I guess that’s the way it started for me. I’ve never been a musician or seriously learned to play an instrument, but, to some extent, I prefer music to film. It’s something I wish I could share in. Especially the improvisational part, where the musicians get together and communicate by sound. They respond to each other and create this whole thing all together. I think that’s what brought me to performance, because it involves controlling an instrument. But instead of sound rhythms or sound vibrations its light rhythms and the physical experience of light.

The music brings something to the image, and the image brings something to the sound, and altogether it becomes a piece. Also, I’ve seen a lot of concerts with extremely sloppy projection. I can remember a couple of instances where the show starts and there’s already a Super 8mm loop running. So you’ve already seen the image, and then the band starts to play a song, the song finishes, and the loop is still running. It doesn’t actually bring anything to the music, it’s just static: it’s a visual accessory. I think there’s a way to deal with the projector, to either physically touch the lens, or create a shadow: doing something along with what’s going on with the music.

BK: In your performances you seem to be working with the projector as an instrument.

KL: I guess. What I do, with the hand-painting part, when I paint over film while it’s running through the projector, or when I throw bleach on the film while it’s running through, comes from seeing the work of Pierre Hébert. For instance, the performances he did with a single 16mm projector, where he was taking the loop and placing it on a light table and drawing on the film directly while it was running–he had maybe three seconds to do something–then he would take another part and draw on it.

BK: Was this one of his collaborations with Bob Ostertag, or was it prior to that?

KL: It was prior, but I’ve seen one where he would scratch film to Bob’s music. But from there they moved to the Between Science and Garbage project, shifting completely to digital. At one point he was mixing digital and film as well. I don’t know how long he did that for. But he’s been doing projector performances since the 70s, I think. And he’s done many collaborations with people like Jean Derome and many other musicians, including Fred Frith and John Zorn in New York.

BK: I’m interested in how you actually produce the footage that you use in the performances. Do you contact print found footage?

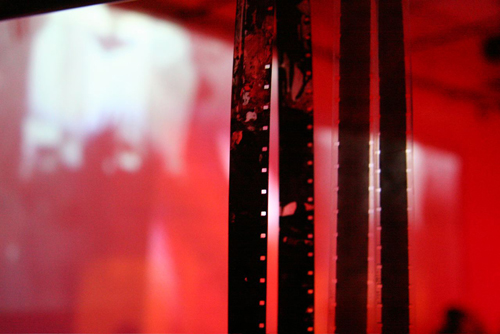

Detail of film loops / Photo: Nicolas Bilodeau

KL: It depends. I like to shoot my own footage as often as I can and manipulate it live. I have a little collective now with Alexandre St. Onge and Jonathan Parant; we’re planning to do a series of performances together. All of the footage comes from a weekend we spent in the countryside. We shot maybe ten rolls of Super 8. In addition to music they also do other performance work, in the tradition of physical performance art. So I was shooting one of their performances in the forest. From there I will optically print that material to 16mm, then contact print and hand-process it, and make loops from it. Those loops are what I use in the performances.

In the performances with Jerusalem in My Heart [Radwan Moumneh], there are some handmade filmstrips, either hand-painted or made by transferring imagery from paper to film. There are also text and flicker strips of film. Some of the footage is based on an Arabic theme; there’s not much I can shoot here on that theme, so I end up using found footage. Then I re-photograph, hand-process, contact print, hand-process again, and transfer to hi-con depending on the footage.

BK: How did you begin working with Radwan?

KL: It started with a performance I did in 2004 for a small art event on the theme of the Western. I had two reels of an American spaghetti western, probably from the 1920s or 30s. Maybe it was from Italy, but it had English inter-titles. I liked some of the footage so I decided to make a short film piece with it. The recording of the sound for the performance wasn’t exactly what I wanted to use for edited version of that material. Radwan was my neighbour at the time. At some point he told me if I ever needed sound or music, to just ask him; he said it would be a pleasure.

BK: Had he seen any of your work prior to that?

KL: Never. [Laughs.] We just got along. But I had seen Jerusalem in My Heart prior to that. He was doing his solo show of electric guitar and voice. It was extremely beautiful–distorted guitar with loop pedal. When I arrived the show had already started and it felt like there were three guitar players on stage. When I realized it was only this one guy I was really impressed. His music reminded me of Neil Young’s soundtrack for Dead Man [Jim Jarmusch, 1995]. There’s something really beautiful about that improvised guitar. Radwan’s concert had a similar quality. So I told him I was doing this experimental found footage film with Western footage, and that I was looking for some kind of free guitar, like the Dead Man soundtrack. And he was like, “Wow, that’s one of my favorite records. I’d surely be interested in doing this.” When he first saw the images I was working with he really liked it.

So we first did that short film together, but it took awhile. I actually didn’t finish it because of some problems at the editing table; I put it on hold. In the meantime he was doing a show and he asked me to join him, to do a performance for his music. That was the show we did for the opening of the Silver Mt. Zion concert in 2006. From that point–it might become a long-term collaboration. We’ve done a couple of shows together; almost every time he plays I bring the projector.

BK: How many times have you performed together?

KL: It was the third performance that you saw in the summer.

BK: What does your practice routine consist of? Do you rehearse together?

KL: For this collaboration we meet and we show each other our work. He burns me CDs; I go to the rehearsals. But I don’t actually rehearse with him/them. We just plan a free structure on which we’ll improvise that night. We also have a cue system for changes, and things like that. We meet and discuss what it’s going to be like, but we don’t actually rehearse. I do rehearsals with this other collective, with Alex [St. Onge] and Jonathan. I rehearse as well with Transylvania. Those are the three projects I’m mostly involved with these days.

BK: Do the musicians that you play with–Radwan in particular–have any input into the imagery you use in the performances?

KL: Yeah, absolutely. Of course, I’m totally free to do whatever I want to. But I wouldn’t just throw any image on the screen. With those three different collaborations, I have a bank of images for each. Apart from some mutual hand-painted material, or stuff that isn’t related to any particular theme, I just build on these images banks for each project. And, the music that they do inspires what I will create for that particular collaboration.

BK: Do you think at all about the meaning of the imagery that you’re using?

KL: As much as I can. For instance, the performance I did opening for [the UK film artist] Guy Sherwin. There was actually a small technical problem. The filmstrip I wanted to burn for that final part–

BK: The imagery of the Queen?

KL: Yeah. I was supposed to use something else and it broke right before I could use it. So I ended up grabbing something else, which I thought was something different than what I grabbed. [Laughs.] That’s how I ended up burning the Queen for 10 minutes! But actually, it brought another meaning to that performance. It was kind-of out-of-control at the time.

BK: That’s amazing, because the synthesis of form and content in that performance was so tight.

KL: That performance went further than anything I did before. With time I gain more and more control over what I’m doing. It’s easy to fuck up. It’s fragile. I mean, you’re not supposed to paint on a filmstrip while it’s running in a projector. Fresh paint, not even dry, goes in the gate and sometimes skips, jams.

BK: You’re not supposed to grab the film while the projector’s running, either.

KL: No, no. Destroying the sprockets, it can easily break.

BK: Do you worry about technical failure? And do you have a contingency plan in case something goes wrong? Is that why you use the four projectors?

KL: Yes, because it’s rare that more than two are running at a time, sometimes three. But while some are running it allows me to prepare the others. So if something wrong happens, I have back-ups. It’s happened in the past: a bulb burned out. It put me in an embarrassing position. I can’t really stop during a performance, but I need to do this change. It requires back-up.

BK: Do you worry about damaging the equipment that you use?

KL: Not at all: I buy projectors especially for this. I wouldn’t show a clean film print on these projectors. They’re basically in my hands to be destroyed. [Laughs.] Inevitably, at some point they will break. I try to keep them in order: I clean them a little bit.

BK: During the performances, I imagine your primary preoccupation is keeping everything on course, and moving, changing loops and so forth. But are you also aware of how the audience is responding?

KL: While doing the performance? [Pauses.] No, I try to focus as much as I can on the response of the musicians. Especially in situations where all of the music is improvised, I try to listen as much as possible to the sound.

BK: So you’re responding to what the musicians are doing?

KL: As much as the musicians are responding to what’s going on with the image.

BK: There are only so many things that you can adjust or do to the footage while it’s running through the projector, no?

KL: There are limits. Say I would like to show a specific image at a particular moment, when something comes in with the music. I need a little time to be able to do that change. Or if I know a change in the music might be coming, I’ll have the loop prepared on another projector ready to run. But sometimes it’s a bit off. That’s why that cue system could be very interesting. I know when to prepare when I have the cue. Then I can tell the musicians that I will soon be ready, to keep that communication going.

BK: Is the length of a performance predetermined?

KL: Sometimes it is. The most beautiful way to calculate the length is by feeling. We know intuitively when one part is over. We feel it all together and move towards something else. When these things happen all together it’s extremely interesting to me; it feels like we’re connecting and moving towards the same place.

BK: What impresses me most about your performances with Jerusalem In My Heart is their emotional intensity and “thickness.” The compact duration really reinforces that for me. I don’t think you could sustain the same feeling over an hour or two hours. That’s what I come away with, that and the physical aspect of the experience.

KL: Yeah, in the sound especially. Jerusalem In My Heart likes to play loud. There’s also a drone aspect to what they are doing, so it really becomes physical sound-wise.

BK: What you’re doing is physical, too, and that’s translated into what the viewers are seeing on the screen, and impacts our emotional response to it. It’s very tactile and haptic.

KL: If I were to try to do the same performance without the sound, it wouldn’t be the same. The sound gives me an empowering energy. It almost brings me to a state of trance. I can feel it in my body. Sometimes my hands are almost shaking as I try to keep going with the work. I realize what’s going on between us–we share something quite powerful. This whole energy kind-of drives me crazy on the projectors. I don’t know how to explain it exactly. [Laughs.]

BK: It’s very serious. It has that impact. It’s heavy and intense.

KL: I agree. The funny thing is, the last time we performed, the idea was to turn it into a party. It was a short performance–it lasted maybe 25 minutes. But it builds up. There was even a drum machine. When we first started to work on the performance the inspiration was Arabic pop music, with the beat box and voices: really cheesy stuff. But those guys turned that into something so serious and overwhelming in emotion. It was quite special to me, because I’ve been following the work of the musicians involved in that performance for a long time.

BK: Who were some of the other musicians that played that night?

KL: There was the Godspeed You! Black Emperor founder, Efrim Menuck, and Thierry Amar, one of the main composers of Godspeed. Those two afterwards founded A Silver Mt. Zion. There was also Jessica Moss, violinist for A Silver Mt. Zion; Eric Craven from Hangedup, who recently became the drummer for A Silver Mt. Zion; Howard Bilerman, who's the sound engineer at Hotel2Tango, the studio where all these guys record their albums. He was also the first Arcade Fire drummer. Will Eizlini, a trumpet player who also does percussion; he's been playing for many years with the Shalabi Effect; and the percussionist Nader Hasan. So altogether we were ten people. The big orchestra thing was quite fun. All these people, I never saw them doing a funny show! [Laughs.] What they do is quite strong in emotion.

BK: It still had a spirit of camaraderie. Even though it was serious and heavy, one could sense that the performers were enjoying each other’s company.

I’m very excited by the new collaborations that are going on between Montreal’s experimental filmmakers and musicians. You’re an important hinge, bringing these two scenes together. It seems there’s more crossover now than there was maybe five years ago.

KL: It did happen back then, but in isolated circumstances. Maybe it’s still like that, I don’t know. Yeah, there’s something going on now. It’s interesting that this is starting to happen, because most of these musicians really like experimental film. But they don’t necessarily know how to get that information, since they’re heavily involved with the music scene; that’s their main focus. Then you have filmmakers that are in the film world, they don’t know much about music. But more and more, it seems like both universes are encountering each other.

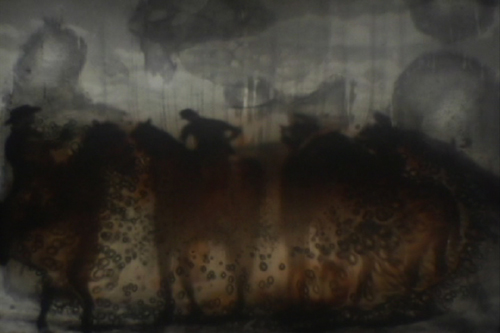

Western Sunburn / Karl Lemieux

BK: Tell me about Western Sunburn (2007). Is the imagery in that piece documentation of a performance, or was it projected and performed to camera to be edited into a finished piece?

KL: I did the performance in September 2004. From that, I had this film loop still in the can. I liked some of the images a lot. Some were heavily modified with bleach and paint, so there was something really dirty about it. Some of the images had silhouetted, recognizable figurative imagery behind that modified, handmade film surface. I knew I wanted to use some of that to do a piece. The only way to transfer the material was to re-do the performance, because the documentation of the performance included people watching the show and musicians playing and the crowd itself, and the camera shaking from one element to the other. It wasn’t usable. I had to sit down and re-photograph these film loops on a screen with a video camera. While I was doing this at some point I started to play more with the technique I used in the performance: Painting even more on the film, bleaching some of these loops even more, and then burning them. That’s the important part, which cannot be captured by an optical printer. At first it was more for archival purposes, and then it became this other project.

BK: I like how the horizontal panning shots are disrupted by the vertical jumpiness that’s caused by the projector. It creates a similar effect to the one in Brakhage’s film Sirius Remembered (1959). In it, he superimposes really fast horizontal and vertical plans, resulting in a type of polyrhythm. The conflicting movements in Western Sunburn reminded me of that. It’s visually compelling.

Does the western hold any special significance for you? I was thinking of the time you spent in the American west.

KL: I spent one year in Nevada. There are a lot of cowboys over there. [Laughs.] Yeah, absolutely. The cowboy theme wasn’t something I originally picked up on. A musician I was working with was creating an homage to spaghetti western films. Meanwhile, a guy at an antique shop gave me these reels and I started to work with them for the performance. That was the starting point. It wasn’t a conscious decision to do something with western footage. But along the way I realized that I like these images. The culture of the American West–its codes–was invented by cinema. It wasn’t camera, photography, reality. Cinema was creating a new kind of reality, which was something quite fake: the whole cowboy image, with the hat and how they were dressing. [Pauses.] But the meaning in those images, of course, is something that everyone interprets differently. [Pauses.] There’s something about the film culture as well that I like. And showing the apparatus over that, like the way you sometimes see the sprocket holes of the film, or even the frame line, or the film burning.

BK: It’s interesting you mention that, because John Ford was famous for his illusory space, with the deep focus and wide-angle shots: the image as window, the sense that we’re inside the image, breaking down the separation between screen and audience.

KL: That’s how most traditional narrative film works. Through invisible editing and tight storytelling, we’re brought into this space, where we forget that we’re actually watching a film. This created universe becomes like a real experience, something you’re totally focused on. You forget that you’re sitting somewhere following these stories. That’s something I really liked about experimental films when I first started watching them. They revealed the apparatus. There’s no illusion of reality. Rather, they’re showing the material like a sculpture or a painting, where you can almost feel the physical aspect of the medium.

Motion of Light / Karl Lemieux

BK: I have a couple of questions about your film, Motion of Light (2004). It’s fairly long for a hand-painted film–8 minutes–but it has a constant formal progression. I’m curious how you developed those techniques.

KL: At that point I had been drawing for a quite awhile, especially pen-and-ink. When I was 17, I took calligraphy courses. I was particularly interested in calligraphy techniques involving a brush, without actually touching the table, where the hand would be over the paper. I was trying different things, but I wasn’t really happy with the results I was getting. With [the earlier film] Chaos (2002), for example, you see the things I was trying at that time, such as straight lines of ink. There’s something only two-dimensional about it. Whatever I was trying at that point was always about absences or presences of light, like shadows or spots here and there. It had rhythm, but it was flat. There was something missing. So I kept going.

Meanwhile, I received some new music from a friend. I was listening to it one night and I was really into it. I had a good feeling from it as I was brushing the filmstrip. What’s interesting about that is, if you film a person doing a physical movement, this movement creates a rhythm with the space and the light. But the movement you apply to a filmstrip with ink and brush is imprinted on the film on a microscopic scale. This tiny little frame that you blow up is actually like an extension of that very movement you were doing with the brush. It was fascinating when I first looked at the filmstrips I did with the brush like that on a Steenbeck. I remember staring at these images for almost three hours–and there was only 20 seconds of them! [Laughs.] The way I was working with the brush–at first I was doing tiny, tiny textures using continuous movements. Before it was dry, I would do bigger strokes at the end. So it would create this perspective in which you can feel that something is way further than what’s in the foreground.

BK: So you were starting to work in a more gestural way on the filmstrip.

KL: Exactly, starting with those tiny textures, then doing bigger movements at the end to create bigger strokes over it before it was dry. So the bigger strokes erase the smaller ones at the end, but you can still see some of these tiny little textures underneath; some that are not as big as those ones at the beginning, playing with that. I kind-of did this by accident; it took me another two weeks to go back to what I did before to understand exactly how I did it. I was trying over and over and I never got the same result until I actually figured out what I had done. Then, those brush strokes kept going for 10 months; the film was born from that.

BK: When you’re working with musicians, do you ever feel there’s a struggle between the image and the sound? In Motion of Light, there are moments when the music seems to dictate the rhythm. At the very least, it shapes our perception of the film’s visual rhythm.

KL: Yeah, it does, just as the image shapes our listening of the soundtrack. If we were to listen to the music by itself, it would be a completely different experience. It adds something, but it takes something away as well. Some people would probably prefer the film without the sound. Some people think they go extremely well together. It’s a matter of perception.

In the case of Motion of Light, I wanted to create something with pure noise: abstract imagery with abstract sound.

BK: One of your earlier films has a soundtrack by Lee Ranaldo. How did that happen?

KL: I was still in high school at the time. Sonic Youth was an important influence when I was younger. I was listening to their music a lot, and at some point I got interested in their more experimental projects, like Lee Ranaldo’s solo material. I got the chance to shoot my first short film in Nevada, while I was in school there. They had a VHS camera that we could use to make a short video piece. When I started to write and work on it, it was inspired by one of Ranaldo’s songs. It was a spoken word piece called “The Bridge.” It’s funny, because when I arrived down there I couldn’t speak English very well. I had trouble understanding what all the words meant. I was writing everything down to figure out what the piece meant. I could understand most of it: that it was about him and his father going in this old Chevy pick-up truck, delivering some furniture to his brother, or something like that. I found one of these old trucks–it was a GMC, not a Chevy, though. But I found this truck, and I was in the desert. The picture on the cover of the album was a photo by Ranaldo’s partner, Leah Singer. It was a black-and-white photo of an old truck in the Nevada desert, where I was basically. All these things came together at once.

It wasn’t until a couple of years after I had finished the film that I finally understood why it was called “The Bridge.” What he’s actually talking about in the song is crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. [Laughs.] I completely missed that part in my interpretation of the piece. The nice thing about it, though, is that my teacher insisted I send Ranaldo a copy. I was a bit shy doing this, so we wrote the letter together and we sent it to him. I didn’t expect him to write back, but he actually did. He wrote me a letter, saying that he liked the film. I was extremely pleased by his response: it was by first piece, so it meant a lot to me.

Karl Lemieux – Filmography

All films produced, conceived, directed, shot and edited by Karl Lemieux unless otherwise noted.

Quiet Zone (working title)

In progress, black-and-white and color, 35mm

Co-writer and co-director: David Bryant

Producer: Julie Roy, National Film Board of Canada

Editor: Charles-André Coderre

Original music: David Bryant (Godspeed You! Black Emperor)

Distributor: National Film Board of Canada

El Camino

2011, 3:20 minutes, color, 16mm to HD

Images : Richard Kerr

Editor: Charles-André Coderre

Music: HRSTA (Michael Moya)

Trains

2010, 5:30 minutes, black-and-white, 16mm to HD

Editor: Fréderick Maheux

Original music: Félix-Antoine Morin

Mamori

2010, 8 minutes, black-and-white, 35mm

Producer: Julie Roy, National Film Board of Canada

Editor: Mathieu Bouchard-Malo

Original music: Francisco Lopez

Distributor: National Film Board of Canada, Light Cone

Passage

2008, 15 minutes, black-and-white, 35mm

Producer: Karl Lemieux, Rodrigue Jean and Nancy Grant

Cinematography: Mathieu Laverdière

Editor: Mathieu Bouchard-Malo

Original music: David Bryant (Godspeed You! Black Emperor)

Cast: Brigitte Pogonat, Francis Ducharme, Genevive Ouellon and Mathieu Bourguet

Trash and No Star!

2008, 6 minutes, black-and-white and color, 16mm to miniDV

Co-producer, co-director and co-editor: Karl Lemieux and Claire Blanchet

Music: Dreamcatcher (Katerine Kline and Blake Hargreaves)

Distributor: Cinéma Abattoir

Western Sunburn

2007, 10 minutes, black-and-white and color, 16mm to miniDV

Original music: Radwan Moumneh (Jerusalem In My Heart)

Editor: Daïchi Saïto

Distributor: Light Cone, Cinéma Abattoir, Vidéographe

Mouvement de Lumière/ Motion of Light

2004, 8 minutes, black-and-white and color, 16mm

Original music: Olivier Borzeix

Distributor: Light Cone, Cinéma Abattoir, Vidéographe

Monophobia

2003, 8 minutes, black-and-white, 16mm

Production: Concordia University

Cinematography: David Boivert

Music: Daniel Menche

Chaos

2002, 4 minutes, black-and-white, silent, 16mm

Production: Concordia University

Cast: Marie Brassard

Untitled – Silos

2003 - 2011, 3:20 minutes, black-and-white, Super 8mm to HD

Editor: Charles-André Coderre

Music: BJ Nilsen & Stilluppsteypa

KI

2001, 3 minutes, black-and-white, Super 8mm, silent

Distributor: Cinéma Abattoir

The Bridge

1998, 3 minutes, color, S-VHS

Production: Galena High School

Narration and music: Lee Ranaldo

Editors: Karl Lemieux and Robin Tanner

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brett Kashmere is a Pittsburgh-based filmmaker, writer and curator. He is also the founding editor and publisher of INCITE.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Manifest