God Must Have Painted Those Pictures: Illuminating Auroratone's Lost History

By Walter Forsberg

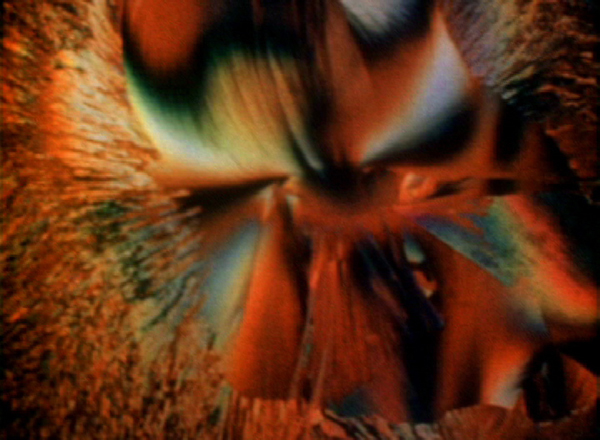

"When the Organ Played 'O Promise Me' " Auroratone / Cecil Stokes, courtesy of Robert Martens

A Queens art teacher by day, Robert Martens also manages the YouTube channel Grandpa’s Picture Party, posting video transfers of home movies and films shot by his late grandfather Gus, who had been an avid member of the Amateur Cinema League. I first met Robert in 2011 at New York City’s Home Movie Day, where he screened some footage that Gus shot at the 1939 World’s Fair. We got to talking and our conversation quickly turned to one of the most bizarre items on the Grandpa’s Picture Party channel: a three-minute sound film of shifting colored patterns. The work was an uncanny and perplexing thing, akin to Brakhage-on-Valium, and it inspired the same kind of prolonged fixation as crackling campfire or one of those enchanting moving waterfall pictures. Robert had never been able to determine exactly what it was, and in 2007 he posted the movie under the title Psychedelic Bing Crosby Video hoping someone could shed light on it. As he told it, user comments for the first couple of years were amusing (i.e. “What was Bing smoking?!”) but far from helpful. Many questioned the movie’s authenticity. Finally, he received a very brief comment from username “bunnyhatter” suggesting that it was an “Auroratone.”

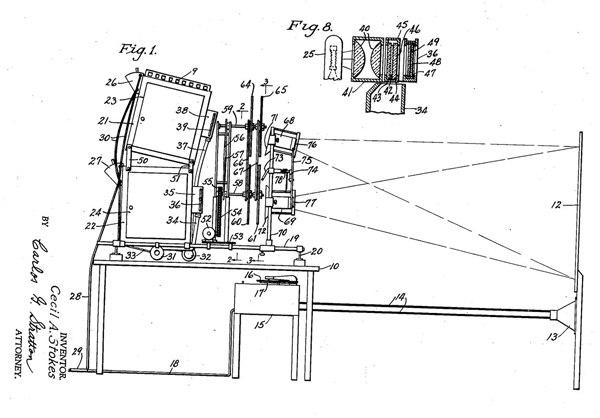

Auroratone was the result of mechanical attempts by British-born Cecil Stokes to render music into projected colored images. The key idea here – mimicking synaesthesia with the help of machinery – dates at least as far back as French Jesuit Louis-Bertrand Castel’s 18th century “ocular harpsichord,” which correlated colors of the visible spectrum with notes of the musical scale. [1] In 1940, after some six years of research and development, Stokes applied for a patent called, “Process and Apparatus for Producing Musical Rhythm in Color”: [2]

| a process and apparatus by which the effects of musical rhythm may be reproduced in visible colors... to produce a flowing rhythm of color synchronized with the rhythm of the music that produced the color medium… to produce light in motion that is synchronized with rhythm of music. [3] |

U.S. Patent drawing for Stokes' “Process and Apparatus for Producing Musical Rhythm in Color”

By August 1942, when Stokes finally received patent #2,292,172, he had already debuted his projection machine at an American Legion post in Long Beach, California. [4] A rare layperson’s explanation, by the light artist John Sonderegger, elucidates how Stokes used sound waves from audio loops to create the colored slides of crystalline patterns:

| [Stokes'] procedure was to cut a tape recorded melody into short segments and splice the resulting pieces into tape loops. The audio signal from the first loop was sent to a radio transmitter. The radio waves from the radio transmitter were confined to a tube and focused up through a glass slide on which he had placed a chemical mixture. The radio waves would interact with the solution and trigger the formation of the crystals. In this way each slide would develop a shape interpretive of the loop of music it had been exposed to. Each loop, in sequence, would be converted to a slide. Eventually a set of slides would be completed that was the natural interpretation of the complete musical melody. [5] |

Yet unclear, was what became of Stokes’ and his projection contraption. Aside from the patent, references to Stokes’ origins and biography were scant, and Auroratone proved remarkably absent from scholarship on experimental film, expanded cinema, and film history in general. (Even the connection between bunnyhatter’s suggestion and Stokes’ mechanistic invention seemed tenuous, as the term “Auroratone” fails to appear in the text of Stokes’ patent.) Why did Bing Crosby’s voice accompany images that in some other era – say, the 1960s – might screen to a bunch of drugged-out dancing hippies at Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium? How exactly did images generated by Stokes’ elaborate light machine end up on 16mm Kodachrome film stock? And, why did Gus Martens, a Queens soda pop distributor, possess the only-known Auroratone print? This exhibition history attempts some answers.

* * * * *

During the 2012 Orphan Film Symposium, the Museum of the Moving Image hosted a public screening of Martens’ unexplained Auroratone artifact. Martens was on-hand to introduce a new 16mm preservation print of the film, and he described his own first encounter with the film:

| Good evening, it’s a real delight to be here. When I first saw this movie I was just a kid, and I had no idea what it was. The year was 1968. The place was Queens. My grandfather’s film projector was silent, but on one occasion he borrowed a sound projector to show us the one – and only – movie reel from his personal collection that had a soundtrack. It was a World War II-era live action novelty short titled, Archery Antics, and us grandkids were very amused by it. Right after this short, there was this weird little sequence of shifting color patterns. Us grandkids, being kids, had no clue what we were looking at. “What is this, Grandpa?,” we asked. All he could say was, “Gee, I don’t know… just something I picked up’.” |

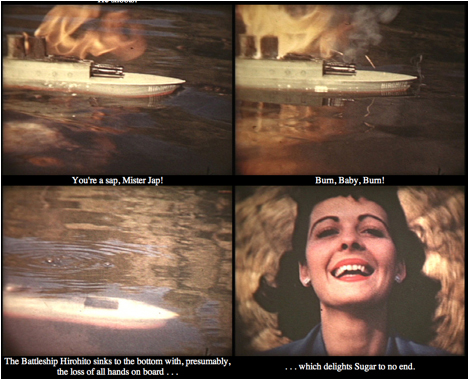

Archery Antics is nearly as mysterious as the Auroratone itself. Yet, Robert’s mention of the two films’ provenance connection revealed a common thread between the Auroratone and “psychodramatic” films shown to psychiatric patients during World War II. Made by the sponsored film producer Don Robert Catlin, the nine-minute Archery Antics opens with (as the narration describes) “a shady lagoon, a swing, a beautiful girl, and a roving archer,” played by the world-famous archer Ande Vail. After Vail bullseyes a red balloon attached to the buxom female’s toe, the couple engages in a host of exhilarating acts: target practice, match-lighting, and feasting on an elaborate spread of picnic food. “I’ll bet they don’t feed you this good in the army,” the narrator speculates. The film ends – insanely – with an alarming periscopic close-up of a toy battleship floating in a nearby pond, emblazoned with the Japanese flag and the name “Hirohito.” In a drawn-out tension-filled finale, Vail shoots an arrow sinking the boat in a fiery flurry, while Rossini’s thundering “William Tell Overture” climaxes on the soundtrack.

Stills from Archery Antics / Don Robert Catlin, courtesy of Robert Martens

During World War II, Army psychologists began experimenting with the use of specialized movies in wartime hospitals as therapy for “combat fatigue” – what we acknowledge today as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Films could cathartically trigger traumatic memories during therapy sessions and, according to Lieutenant Commander Howard P. Rome (one of the most prolific published scientists on the subject), such screenings were first prompted by the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery in 1943. [6] Categorized as either “therapeutic” or “psychodramatic,” these films were carefully scripted by psychologists to portray tailored, “scenes of action, role developments, climaxes, and anti-climaxes. [7]

Archery Antics’ production era and its gargantuan degree of non-sequitur pathos makes it a likely candidate as one such psychodrama. When I suggested this to Robert, he amazingly recalled:

| Well, during the 1940s, Gus did supplement his income with a part time job showing movies to patients in mental institutions. He and a friend would take rented movies and a projector with them in a car to the institution, set up the projector in a convenient room, and give the show. As per my father's recollection, Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens, New York was definitely one of those institutions he visited. |

Indeed, medical literature reveals that Stokes’ Auroratone technology figured notably in psychiatric healing, largely through the work of the army psychologists Dr. Herbert E. Rubin, Captain, M.C. and Dr. Elias Katz, 2nd Lt. MAC. Results of their testing, first published in 1946, detailed Auroratone’s ability to stimulate intense relaxation, weeping, and emotional catharses in patients that enabled them to speak freely with psychiatrists immediately after screenings – conceivably, the kind of visual soothing required by patients witnessing Vail’s tense “defeat” of the Japanese navy. [8] So effective were Auroratone’s patterns of light and music, that Katz and Rubin posited that sensitivity to aesthetics was an instinctual vestige that could transcend psychoses.

Katz and Rubin’s research was preceded by several other cursory Auroratone experiments. Reports in 1944, from the Seattle nurse Marjorie Umbenhour, R.N., tell of screenings in the locked wards of military hospitals that resulted in one-third of patients falling asleep. [9] “Why don’t they give us more stuff like that?” one vet asked. “After seeing these movies,” another said, “I’ll never doubt God again.” [10] Subsequent testing in 1951 by two Michigan doctors from the Lapeer State Home and Training School reported that Auroratone only further agitated a clinical group of “female psychotics;” had no therapeutic effects on “low-grade male patients of disturbed character;” but, did produce a “reverie-like hypnagogic state” in certain members of a third clinical group of “moron grade-school children.” [11] Initially prescribed for the mentally afflicted, post-war Auroratone treatments were soon adapted for social miscreants as well. At a Los Angeles home for troubled youth, one juvenile delinquent responded to a screening: “I think God must have painted those pictures. ”[12]

"When the Organ Played 'O Promise Me' " Auroratone / Cecil Stokes, courtesy of Robert Martens

"When the Organ Played 'O Promise Me' " Auroratone / Cecil Stokes, courtesy of Robert Martens

Auroratone prints found their way into these experimental testing milieus thanks to the establishment of the Auroratone Foundation of America (AFA) in March of 1944. [13] A California state non-profit, the AFA’s stated mission was to discover, “new and improved methods of lessening mental and physical tensions in the shortest possible time, and in natural ways,” and benevolently distributed its services free of charge. [14] At its founding, Cecil Stokes was appointed AFA chairman, Bing Crosby became Director of Music Research Experiments, and Mary Pickford was cited amongst its original board members. [15] Crosby’s affiliation with Stokes provided soundtracks with which to generate Auroratone’s crystal patterns, and his fiduciary liens enabled the initial creation of film print versions of Stokes’ projected patterns, for wider dissemination.

While the partnership may seem initially outrageous, Crosby’s colossal wealth as America’s preeminent entertainment personality would deeply impact the development of experimental media, even subsequent to his involvement with Stokes’ Auroratone. Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE), headed by Crosby’s brother, Larry, saw major shareholding investment of Crosby’s cash in a strange array of banal business collaborations, including: special window-sash holders, automatic coffee dispensers, Minute Maid frozen orange juice, and the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball club. [16] But, Crosby also supported funding of the U.S. Army Signal Corpsman Jack Mullin’s experimental research with magnetic audiotape plundered from the Nazis – technology which enabled Crosby to pre-record, overdub, and easily edit his radio show. This latter investment would forever transform the industry of recorded sound and, in 1956, resulted in the first commercial release of videotape – at the time, perhaps, an equally far-fetched parallel effort at technologically converting sound into moving images.

In June 1944, Crosby made Auroratone recordings of “Going My Way,” “Home on the Range,” and “Ave Maria” with organist Eddie Dunstedter. [17] (Lt. Col. Dunstedter, AAF, who later appeared on AFA letterhead as “Director, Musical Arrangements and Recording,” was active in Hollywood film scoring circles and as an occasional accompanist for Crosby.) Stokes would later tell a Sandusky newspaper that “Bing Crosby recorded the first songs for us, free,” adding, “and paid everything we needed to send them overseas. They tell me they were shown every place – from battle lines to death beds.” [18] Reports suggest that Bing Crosby went so far as to learn “Chinese lingo” to record an Auroratone of China’s national anthem, at the request of Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek. [19]

No hard evidence exists to explain Stokes’ initial encounter with Crosby, but the “Women’s Page” of the Lubbock Morning Avalanche cites a Crosby-influenced Genesis story for Auroratone. Stokes was recuperating on a friend’s yacht, from ulcers developed as an advertising executive, when:

| The deck steward was playing some of Bing Crosby’s records and Mr. Stokes became mentally lost in the movement of reflected colors of the sunset, combined with the soothing tones of Bing’s voice. Afterwards he felt very much relaxed and inspired. He was able to sleep without the use of a sedative for the first time since his illness. [20] |

* * * * *

Throughout the 1940s, women’s groups like the Bakersfield Soroptimist Club and Woman’s Club of Hollywood sponsored fundraising efforts to finance the production of Auroratone film prints meant to treat returning war veterans. [21] In an attempt to convey Auroratone’s immense powers, a 1945 Long Beach Press-Telegram article included a first-person testimonial from a B-29 bombardier:

| […] I thought I saw a cave lined with mother of pearl; from out of this cave poured liquid gold fringed with jade green; this then turned to a golden yellow and then the entire scene receded into a sea of blue which swallowed it up only to be replaced by a huge flower with petals which dripped magenta. [22] |

Cecil Stokes was often a guest at these fundraising exhibition-galas, speaking alongside army nurses and society members. After one such screening, Mrs. Laura James DeWitt documented her Auroratone experience in Rosicrucian Digest, poetically echoing other first-person testimonials of the era: "Can this be the doorstep into another world – a world of inspiration and knowledge of why things are as they are?" [23]

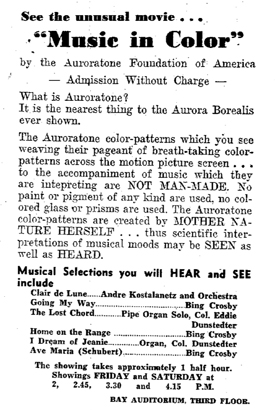

The network of Auroratone exhibition throughout the 1940s spanned the continent outside hospital and philanthropic venues as well, with frequent public screenings in department stores: at L.A.’s Broadway in 1943 (promising the “scientific sensation of the day” [24]); at Philadelphia’s Snellenburg’s in 1945 [25]; in the tenth-floor auditorium of L.A.’s Bullock’s in 1947 [26]; and at Winnipeg’s The Bay auditorium, where the event was heralded as “the nearest thing to the Aurora Borealis ever shown.” [27] For screenings at Chicago’s The Fair in 1945, newspapers promoted the screenings with the tagline: “you’ll probably feel sleepy yourself.” [28]

|

|

L to R: Advertisement from the Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1945, 7; advertisement from the Winnipeg Free Press, September 18, 1947, 16.

The film scholars Caitlin McGrath and Liz Czach have demonstrated how large department stores established seasonal subscriptions for film and lecture performances in extravagant auditoriums, in an effort to make the stores a social hub of activity. [29] Lecture-screenings by independent travelogue filmmakers in the mid-20th century were the most common department store fare, and Auroratone’s appearance there may be explained by Stokes’ acquaintance – at early Los Angeles-area women’s club screenings – with Father Bernard Hubbard, a Jesuit known as the “Glacier Priest” who was an explorer, photographer, missionary, and highly-paid lecturer. [30]

The connection with Father Hubbard resonates with another of Auroratone’s exhibition paradigms, one tied both to religion and the same Amateur Cinema League that Gus Martens was a member of. Stokes’ first appearance on the historical record comes in 1927, writing an article for Movie Makers – the monthly journal of the newly-formed Amateur Cinema League – called, “Films for the Church.” Stokes’ profile shunned church technophobes and declared a “new role for the amateur,” while highlighting souls engaged in the “formation of cine clubs… to further bind parishioners to their religious duties and advisors.” [31] Stokes proclaimed “there is a formative power in the cinema which neither the living voice nor the printed book or paper possess... films for the church are here to stay, and to grow immeasurably in importance.” [32]

Illustration for Cecil A. Stokes, “Films for the Church: A New Role for the Amateur,” Amateur Movie Makers 2, no. 9, (Sept. 1927): 18-19.

As the multimedia blitzkrieg of any contemporary stadium-grade mega-church service can attest, Stokes’ predictions proved visionary. The 1920s were a pivotal decade in the relationship between religion and the movies in the United States. Against the backdrop of temperance movements and the eventual adoption of the Motion Picture Production Code in late-1929 and 1930, national church leaders were seeking to insert themselves into the realms of cinema production. Yet, church meddling in movies was not only aimed at regulating social mores through censorship. “Clergy from a variety of established denominations were also eager to capitalize on what they perceived as the innate attractiveness of motion pictures to their audiences, especially children,” writes the film historian Anne Morey. [33] The appearance, in 1923, of Kodak’s 16mm format undoubtedly influenced this upturn; originally intended for domestic use, the format eventually saw wide employment in educational spheres. [34]

|

|

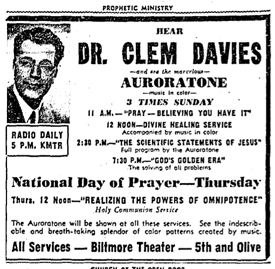

In fact, some of Auroratone’s first public screenings were as illustrations for sermons by cultish preachers in Los Angeles’ burgeoning 1940s charismatic social gospel scene. Reverend Dr. Clem Davies, a pioneer in radio broadcast evangelism, shared in Stokes’ zeal for using “new media” like 16mm film to reinforce religious messages, and was but one such clerical client. In 1941 and 1943, Rev. Davies employed Auroratone projections to illustrate his sermons and associated monstera deliciosa on topics like, “THE SCIENTIFIC STATEMENTS OF JESUS,” “THE COMING PLANETARY INVASION,” and “WHEN THE RUSSIAN BEAR REACHES GERMANY.” [35] Auroratone was also used by religious leaders in 1942 Easter services for the First Methodist Church of Hollywood, and 1943 services at Foursquare Church (a denomination founded by fellow broadcast evangelist Sister Aimee Semple McPherson), among a handful of other church screenings. [36]

Within this array of diverse exhibition contexts, Auroratone might be best considered part of what the film scholar David E. James calls a “fugitive and ephemeral” “minor cinemas” of Los Angeles – a prolific “rainbow coalition” of assorted amateur film works made in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, representing “a more substantial noncommercial use of the medium than at any other time, including the 1960s…” [37] Indeed, the entwined Auroratone exhibitions amid L.A. art societies, evangelical churches, military mental asylums, and commercial shopping centers provides a bizarre exhibition legacy. But, as James’ shockingly prescriptive research shows, thanks to a “close adjoinment at this time of amateur and professional practices,” Los Angeles witnessed, “perhaps, several thousand nonprofessionals in the Southland… seriously committed to filmmaking that approached professional standards of technical and aesthetic accomplishment.” [38]

By 1947, evidence suggests funding for Auroratone-related efforts was drying up. In November, AFA Director of Medical Research Robert C. Welden expressed the need for a grant to expand the AFA’s work with the Veteran’s Administration. [39] Welden wrote to the Guggenheim Museum’s co-founder Baroness Hilla von Rebay offering an introduction to “a new technique using non-objective art and musical compositions as a means of stimulating the human emotions in a manner so as to be of value to neuro-psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as to teachers and students of both objective and non-objective art.” [40] With no response, and the AFA’s Christmas stocking empty, Stokes followed up Welden’s inquiry in late-December, requesting funds from Rebay to conduct research “in the field of abstract painting and design and the reactions of human personalities,” including Auroratone testimonials and photographs. [41] The Baroness eventually responded to the AFA with a lesson in aesthetics, free of charge:

| You should first of all learn what is decoration, accident, intellectual confusion, pattern, symmetry, as all this is in these photos – all of which has no relation to Art and no influence whatsoever on the onlooker… There should be no accidental charm either; in art there is conceived law only –never an accident. [42] |

The Guggenheim Foundation was more interested in Thomas Wilfrid’s “Clavilux” color organ, and von Rebay denied the AFA research funding. In 1948, the BCE’s Larry Crosby also publicly hinted at the financial incertitude of the AFA, telling a Missouri newspaper: “therapeutic experiments are expensive and unprofitable.” [43]

By 1955, now, operating under the aegis of the Harmonic Sonic Research Laboratories of Los Angeles, Stokes traveled to Reno, Nevada to plan Auroratone recordings for “The Bible in Color” with a group of twelve churchmen. [44] After this, Stokes and his Auroratone disappear entirely from the public record. No trace of textile and ceramic merchandise emblazoned with Auroratone patterns – as once publicized by Larry Crosby – are known to survive. [45] Also gone are reverse engineering attempts, which Stokes claimed to be developing, at rendering photographs of the Grand Canyon into audible harmonies. [46] Hospital maternity wards equipped with Auroratone projections, in an effort to “do away with the pains of child-birth,” seem never to have materialized. [47]

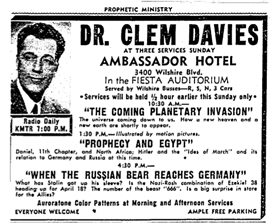

Gus Martens’ original 16mm 1943 Kodachrome Auroratone print, and a new preservation internegative, are now part of the collections of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – an appropriate L.A.-based home for Cecil Stokes’ curious para-cinematic invention. While still checkered by puzzling ambiguities, I want to conclude this germinal attempt at a history of Auroratone with a metaphoric image: the only known photograph to survive of Cecil Stokes (perhaps, holding one of Auroratone’s crystalline glass slides) – a high-contrast and blotchy microfilmic swamp – from the October 21, 1941 issue of the Long Beach Independent, where it publicized Auroratone’s debut.

Advertisement from the Long Beach Independent,

October 21, 1941, 17.

MISSING CHILD LIST OF ORPHANED AURORATONES

The only-surviving Auroratone film print is set to the song, “When the Organ Played ‘O Promise Me’,” sung by Bing Crosby. In the hopes that other examples of Auroratone will be somehow be uncovered, below is a compiled list of other Auroratones known to have existed:

- “Adosto Fidelis,” sung by Bing Crosby

- “American Prayer,” by Ginny Simms

- “Ave Maria,” sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- “Clair de Lune,” played by Andre Kostalanetz and his orchestra

- “Going My Way,” sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- “Home on the Range,” sung by Bing Crosby with organ accompaniment by Edward Dunstedter

- “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” organ solo

- “The Lone Star Trail,” sung by Bing Crosby

- Prelude to “Lonegrin,” by the Philadelphia Symphony

- “The Lord’s Prayer,” sung by John Charles Thomas with music by Albert Hay Malotte

- “The Lost Chord,” organ solo

- “Moonlight Sonata,” played by Miss April Ayres

- “None But the Lonely Heart,” by Lawrence Tibbett

- “The Old Rugged Cross,” sung by the Phil Spitalny all-girl chorus

- “Silent Night,” sung by Bing Crosby

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is dedicated to Kathleen Maguire, who first introduced me to Auroratone. Special thanks to Robert Martens, Dan Streible of the Orphan Film Project, and Ralph Sargent at L.A.’s Film Technology who generously provided in-kind film preservation for the “When the Organ Played ‘O Promise Me’,” in 2012.

NOTES

1. James Peel, “The Scale and the Spectrum,” Cabinet 22 (Summer 2006).

3. Cecil A. Stokes, “Process and Apparatus for Producing Musical Rhythm in Color.” Patent 2,292,172. 4 August 1942.

4. “Music In Colors,” Long Beach Independent, October 21, 1941, 17.

5. John Sonderegger, “Lightshow Slides Part A – The Crystal Effect,” 2005.

6. Howard P. Rome, “Therapeutic Films and Group Psychotherapy,” Sociometry 8, no. 3-4, Group Psychotherapy: A Symposium (Aug.-Nov., 1945): 247-254.

7. J.L. Moreno, “Psychodrama and Therapeutic Motion Pictures,” Sociometry 7, no. 2 (May, 1944): 230-244.

8. Herbert E. Rubin and Elias Katz, “Motion Picture Psychotherapy of Psychotic Depressions in an Army General Hospital,” Sociometry 9, no. 1 (Feb. 1946): 86-89.

9. Ralph Dighton, “Color Music Eases Raveled Minds,” The Washington Post, December 5, 1948, L3.

10. Ibid.; “‘Auroratone,’ New Form of Art, Used in Insane Asylums,” Dixon Evening Telegraph, December 2, 1948, 8.

11. Richard E. McKenzie and Fred Kassner, “The Use of Auroratone Films as a Psychotherapeutic Agent with the Mentally Deficient,” Michigan Academy of Science Arts and Letters, Vol. XXXVII, 1951 (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1952): 497-504.

12. “Make Color Out of Music,” The Hutchinson News-Herald, November 28, 1948, 12.

13. Auroratone Foundation of America. Number: C0194321, Incorporation date: 3/1/1944, Domestic Nonprofit, Van Nuys, CA 91402.

14. Alexander Jones, “Auroratone, Wonder Instrument,” Rays from the Rose Cross: A Magazine of Mystic Light (Rosicrucian Fellowship, 1950): 65.

15. Cecil Stokes letter to Hilla von Rebay, December 30, 1947; “Music Creates Visual Impression, Magazine Says,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 15, 1944, 16.

16. Indeed, Crosby’s investments were so wildly diversified that Judy Schmid, publicist for the Bing Crosby Archive, told me: “Some of the things that Bing Crosby Enterprises invested in back in the 40s were never physically in Bing's possession, and may never turn up,” (e-mail message to author, September 28, 2011).

17. Malcolm Macfarlane, Bing Crosby: Day by Day (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2001), 273.

18. “Ulcer Cure in Color-Tunes: Bing Crosby, Ginny Simms Aid Treatment,” The Sandusky Register-Star News, August 30, 1948, 5.

19. “Bing Crosby Starts Studying Chinese,” Bakersfield Californian, June 28, 1945, 11.

20. “Ulcer Cure in Color-Tunes: Bing Crosby, Ginny Simms Aid Treatment,” The Sandusky Register-Star News, August 30, 1948, 5; Margaret Turner, “The Women’s Angle,” Lubbock Morning Avalanche, August 30, 1945, 4.

21. “Auroratone New Visual Delight,” Bakersfield Californian, February 14, 1944, 4; “Tickets Sell Well for Benefit Film,” Bakersfield Californian, March 8, 1944; “Auroratone Showing Planned by Art Group,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1949, 7; “Dr. Bietz Will Close Series,” Los Angeles Times, May 8, 1949, C3.

22. “In Long Beach Art Circles: Music, Color ‘Marriage’ to Be Demonstrated Here,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, February 14, 1945, B12.

23. Laura DeWitt James, “The Color Trail,” Rosicrucian Digest (1944): 37.

24. Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1943, 7.

25. Advertisement, Chester Times, September 11, 1945, 11.

26. Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1947, A3.

27. Advertisement, Winnipeg Free Press, September 18, 1947, 16; Herbert E. Rubin Captain M.C., Elias Katz 2nd Lt., MAC, “Auroratone Films for the Treatment of Psychotic Depressions in an Army General Hospital,” Journal of Clinical Psychology 2, no. 4 (Oct. 1946): 333-340.

28. Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 22, 1945, 7.

29. Caitlin McGrath “This Splendid Temple: Watching Films in the Wanamaker Department Stores,” (presentation at Northeast Historic Film’s Ways of Watching conference, (Bucksport, Maine, July 24-25, 2009); and, Liz Czach, “Travel Lecture Filmmaking in the Post-War Era” (presentation at Northeast Historic Film’s Wunderkino 2 conference, Bucksport, Maine, July 27, 2012).

30. “Auroratone Showing at School Tonight,” Bakersfield Californian, March 9, 1944, 1.

31. Cecil A. Stokes, “Films for the Church: A New Role for the Amateur,” Amateur Movie Makers 2, no. 9, (Sept. 1927): 18-19.

32. Ibid.

33. Anne Morey, Hollywood Outsiders: The Adaptation of the Film Industry (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 117.

34. Patricia R. Zimmerman, Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 108.

35. Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, December 27, 1941, A2; Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1943, A3.

36. “Southland Plans Easter Pageants,” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1942, A2; Advertisement, Hayward Review, December 21, 1943, 4; “Notes on Long Beach Church Activities,” The Independent, June 20, 1947, 20.

37. David E. James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 4, 13, 145.

38. Ibid., 143, 145.

39. Robert C. Welden letter to Hilla von Rebay, November 27, 1947.

40. Ibid.

41. Cecil Stokes letter to Hilla von Rebay, December 30, 1947.

42. Hilla von Rebay letter to Cecil Stokes, January 5, 1948.

43. “Effects May Be Many: Color Music Puzzles Inventors, Aren’t Sure What They Have,” News and Tribune, November 28, 1948, 18.

44. “Reno Churchmen to Record Sound in Color Film,” Reno Evening Gazette, September 13, 1955, 15.

45. Ralph Dighton, “Color Music Eases Raveled Minds,” The Washington Post, December 5, 1948, L3.

46. Laura DeWitt James, “The Color Trail,” Rosicrucian Digest (1944): 26-27.

47. As suggested in: Alexander Jones, “Auroratone, Wonder Instrument,” Rays from the Rose Cross: A Magazine of Mystic Light (Feb. 1950): 65-71.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Walter Forsberg was born in Saskatchewan and works in media preservation. Forsberg was a co-founding member of L'Atelier national du Manitoba. In 2013 he served as Audio-visual Conservator for the XFR STN exhibition at the New Museum, and is currently working on a series of new films in Mexico City.