AFTER:

A Beginner's Guide to Alchemy

By Carl Brown

I work extensively with the optical printer, using it as a vehicle for compression and expansion of images. By taking a “real” image and looping it, I compress the image by the use of the spring-wound motor of the Bolex camera. I disengage the automatic motor and re-photograph the image, with both the camera and the projector running simultaneously. I make films this way because it involves an interesting paradox.

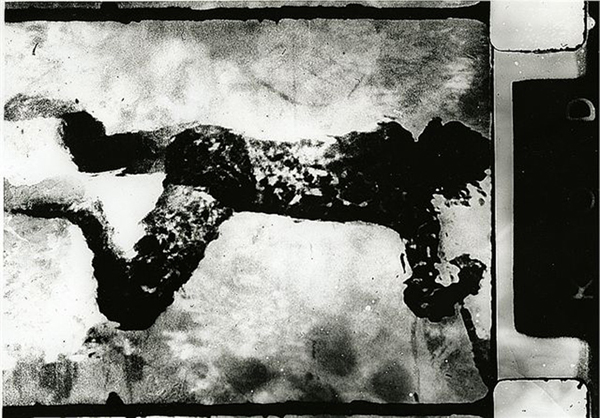

Image: Still from Re: Entry (Carl Brown, 1990). Courtesy of the artist.

Image: Still from Re: Entry (Carl Brown, 1990). Courtesy of the artist.

Beginning with a “realistic” image, either originally made by me, or pulled from compilation footage, I take either the form of the original image, the movement, or the emotional quality as the impetus for selection. I take apart (deconstruct) the realism inherent in the image. This leaves me with an abstraction of form and movement, and I leave the emotional quality of the image intact. I then create a pulsing loop, which seems appropriate for the image in question, and as it fits into the scheme of the whole film. A shot may undergo as many as seven or eight transformations before it is ready to be used. There is beauty in this elongated process. Essentially, every stage becomes a new shot within itself, and can therefore be incorporated into a film structure: one can cut from reversal to negative and through this create the continuity needed for the film to be coherent.

Consider: because the film is so abstract in this form, one must insert something so the audience can follow the film. This can work on the level of the (sub)conscious: the audience perceives the subtleties of film based upon your structure. This takes film into audience members’ minds. Logically, I can make the length of the shot as long as required so the rhythm of the shot is embedded audiences’ memory. This technique has limitless potential; I just begun to tap into it.

As I experimented with this looping process (cycle imaging) more fully, it led me to other fields of motion picture film: the Sabattier Effect (a form of solarization) and reticulation. Jeffrey Paull, my instructor at Sheridan College, introduced me to these processes through Jim Stone’s Darkroom Dynamics, a book designed to take you beyond shooting images into a world of many possibilities. I applied the book to 16mm motion picture film; it was designed for 35mm photographers. Looking back on my filmic infancy, I realize I gained a closer understanding of film as art, physical and mental, from many hours in the darkroom, developing thousands of feet in my clear jug. I saw it happen right there bathed in red light, as the film spoke to me clearly. I think this is why I continued my hand-developing studies.

I began to enter a world that to date has merely been touched upon.

Image: Still from Blue Monet (Carl Brown, 2006). Courtesy of the artist.

Image: Still from Blue Monet (Carl Brown, 2006). Courtesy of the artist.

Why did I choose these processes? How do they fit into my filmmaking? It became apparent that the pulsing halo of the Sabattier Effect (a result of exposing the film for short periods of time while it was in the developer) could be worked into the looping process. I could create a depth of field beyond the original footage. This depth of field was visible after the original motion had been slowed down. The halo or glow became something that would gradually work its way across the image’s highlights. By creating my own depth of field, the abstract shot became more and more my vision. I converted what I saw into what I felt. This was a very important event. I had found a foundation to work, and express myself, from.

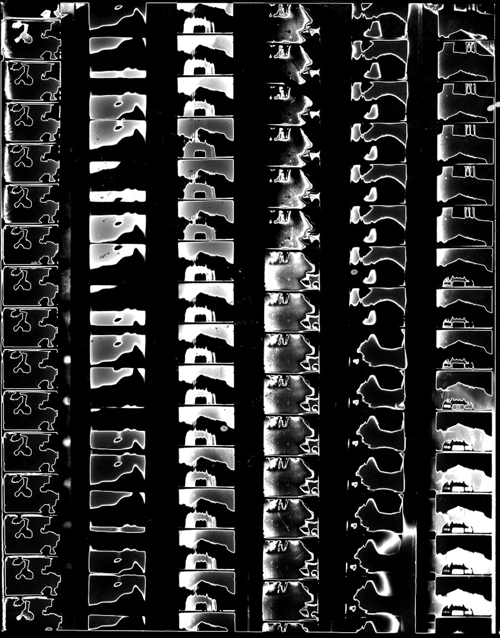

From this point, I began to chip away at the iceberg with a more experienced and knowledgeable eye and approach. I began to reticulate the surface of the film, in hopes that I could create an added dimension to the image. At first, I followed the instructions in the book, but found no success. I was given all kinds of methods from other articles that were involved in this endeavor. One person suggested putting the film in the freezer to crack the emulsion. As it so happened, I stumbled on the right combination after reading various documents on the subject, one being The Dignan Papers on Alkalinity. The first thing was to use a fixer for black and white film, which came with a separate hardener. During the mixing of the chemicals, there is a 32-ounce solution A, which is fixer concentrate to be mixed, and solution B, which is usually four ounces of hardener concentrate. You simply exclude the solution B. This is stage one. Without the hardener, the surface of the film becomes more pliable to work with. The second thing necessary is taken directly from the Stone book, that being, the use of a high developing temperature. For the contrast I wanted, I found that D-19 developer gave me the best results. The developing time of D-19 is approximately five minutes in 64 ounces of developer at 24˚C. Stone’s book recommends 60-65˚C, but I found that all the black and white stocks I was using would usually peel at that temperature, leaving many emulsion flecks and pieces. So, I lowered the temperature until I reached what I found to be a workable temperature. (The temperature is even lower for colour film.)

Finally, I add sodium carbonate to boiling water and submerge the film into the solution for 20 minutes to a week, depending on how radically reticulated I want the image. In order for the reticulation to be evenly distributed across the film’s surface, you must attach the film to whatever surface you intend to pour the solution into. This is a drawback. I use a bathtub; the lengths of my film are no longer than about four feet. I could loop my original image on the printer, shoot off about 50 feet, and then finally process it. Somewhere along the way, I get an original new strand together for the next stage: the extension of the length of the shot. Sometimes I lose footage, but I view this as a blessing. Through the year, I have lost at least two thousand feet of film: original and re-printed shots. Losing the footage forced me to reshape my philosophical approach to film. I do not get as attached to the material knowing I could lose my footage at any moment. My relationship with my film is fleeting. Through this uncertainty, I gained a new flexibility: chance and change.

I primarily worked with printer stocks during this time: 7302, 7362, and 7361. I used printer stock in the camera to achieve the high contrast effect I wanted for the look of my film. These stocks are not panchromatic: I could develop them under a red safelight in a clear plastic jug and watch the progression of the image. Being able to watch the development was also advantageous when I was Sabattiering my film. I could match up one hundred foot rolls of Sabattiered materials that I had done weeks apart. The end result was matching shots! This visibility, you are able to be more spontaneous, more pro-active in the moment. As an artist, you are able to carve out what you really want on the film.

Through the cracking of the image, I could work with minimal motion, long take shots and get additional celluloid motion, which is added onto the 24 frames per second camera motion. This added motion I would call “mind motion.” The reticulation becomes the surface interpretation of the channels that the mind goes through in order for you to stare at any inanimate object for any long period of time. The mind adds the motion in order to capture your inner attention. This could be a subconscious link-up between you and the image, or have no relationship whatsoever with the image: perhaps past memories. The reticulation on film translates this into something visible for the audience, and we actually see it, the subject, and it, the action.

As a person who is lyrical and poetic in my work, I believe that sound in film is as important as image. As I show my films to more and more audiences, I realize sound is something that they can fall back on. The images pass through them in an eye bang or psychedelic effect. Through music, images work on the mind more effectively. Music is a vehicle for the audience to see and feel more through. I have found this to be very successful. Of course, as I more fully mature as an artist, I may find that this is not the case, but my hope is that this marriage of sound and image will have an even fuller range of possibilities. Right now, I believe that sound, used in this way, makes the film more accessible to the audience.

The end result of my work is a 14-minute, 56-second sound film titled URBAN FIRE (1982). This incorporates what I believe is the first sustained reticulated footage in motion picture film, along with the Sabattier Effect, and all the elements I have previously mentioned.

This was my beginning.

Image: Filmstrips from URBAN FIRE (Carl Brown, 1982). Courtesy of the artist.

This article was first written in 1982 and sent to Michael Snow, Stan Brakhage, David Rimmer, Al Razutis, and Norman McLaren. It has since been published in several catalogues including Image Forum (Tokyo, 1991); La part du visuel: films expérimentaux canadiens récents (Avignon, France: Archives du Film Experimental d'Avignon, 1991); Poétique de la couleur, Une histoire du cinéma expérimental, Anthologie (Paris: Louvre Institut de l’Image, 1995); European Media Art Festival (Osnabrück, 2000); Filmprint (Toronto: The Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto, 2006).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Carl Brown, a graduate of Sheridan College's film school, has developed a distinctive style of working in film. Hand-processing and then toning and tinting hi-con stock creates movement, color and texture within the emulsion that is stunning to the eye. His films have shown widely internationally. Brown also works as a photographer, holographer, and writer.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Manifest