The Unstable Eye:

Paolo Gioli’s Film Practice Seen through Paul Virilio

By Bart Testa

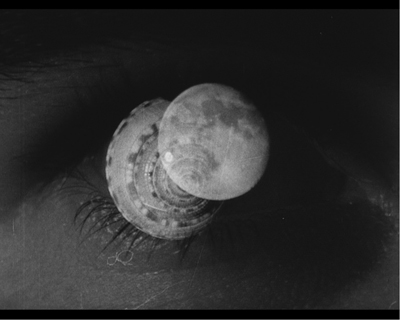

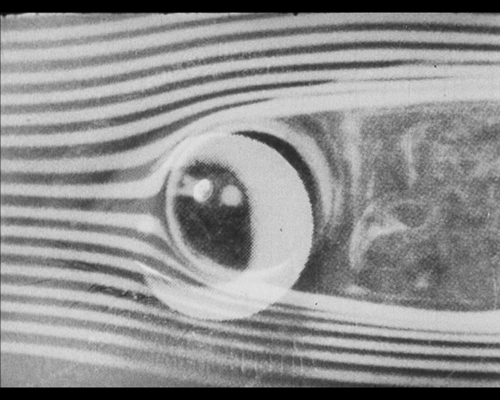

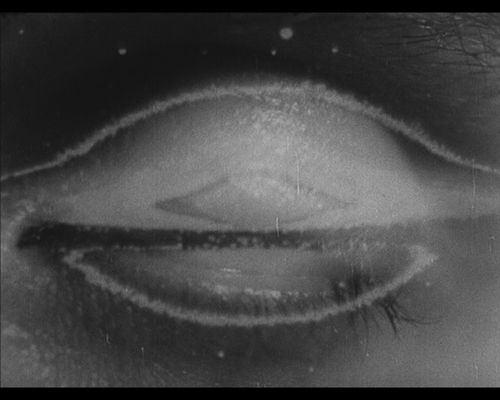

Quando l'occhio trema / Paolo Gioli |

This paper concerns an Italian artist-filmmaker, Paolo Gioli, whose comparative obscurity has hidden him from critical discussion.[1] I hope to glimpse something of Gioli using some bits chipped off a French theorist, Paul Virilio. The incongruity between Gioli and Virilio seems initially extreme.

Born in 1942, Gioli is an artist with an old-fashioned way of working. He has carefully cultivated obsolete ways to use the film camera: he works in 16mm; he hand-edits; he devises home-made optical printing equipment; he develops his own films; he takes a bricoleur’s approach to his camera mechanisms–removing factory-made shutters, for example and replacing these with a (Duchampian) bicycle wheel, a sewing machine, his gloved hand. He has resorted, a bit obsessively, to the pinhole movie camera, devising many of his own vertical designs. The results are that Gioli goes about making mostly soundless, largely black and white films of a slightly disturbing obsolescent imagery and definitely perturbing montage style. In the time-tested manner of experimental film, these are films composed by a cinematic artisan of sur-industrial habits. And Gioli is a first-rate avant-garde filmmaker, perhaps the only Italian film artist to achieve and sustain his level of intellectual and aesthetic accomplishment. One way of comprehending Gioli the filmmaker, because it is a familiar and even conventional experimental tradition, is to approach him as a conscious genealogist of cinema. There are multiple other points of access into Gioli, but this essay limits its attention to just two of his films, rather than attempting a survey of his career. These two probes delve into Gioli’s own imagined version of the image culture that surrounds the cinema, in the vintaged moments of its history, like the era of silent comedy, Andy Warhol’s silent films, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Buñuel and the strangely raw-looking, obscure Italian film materials over which Gioli exercises a connoisseur’s mastery. Because he comes from an obscure corner in the slightly larger obscurity that is Italian experimental film, Gioli should be provincial but he is obliquely conversant with the cinematic adventures of the previous 150 years. And what he draws upon from our visual culture suggests that we should see in his films–and there are over thirty of them–a theoretical participation on Gioli’s part.

Gioli lives in a farmhouse near Bologna, in Lendinara. He seldom travels. He lives and looks like a stolid old craftsman. He is now 67. His best films were made in the 1980s but he was still making very strong films at the start of the new century. He achieved great success for his photo art, exhibited widely in Europe since the early-80s, and widely sought by collectors and galleries. He long ago mastered the motions of the critic-dealer-run art world. His films, which are of similarly high quality as visual artifacts, have rarely attracted parallel attention even when they have been shown alongside exhibitions of his paintings and photographs. It is understood that his densely wrought experimental films and visibly rich stills work demand different viewing skills. But the determining factor is that Gioli’s photographs had an art context, while the almost total disappearance of an Italian avant-garde cinema meant his films had no corresponding support system.

Gioli’s subject matter is not easy to summarize. Though one would be hard-pressed to see him as autobiographical, Gioli makes films from what surrounds him or that he occasionally sets up in his small studio. He also collects: discarded films, TV materials, and plates from black and white art and photo books form a kind of archive. He has made at least three films that turned to his elective ancestry as a filmmaker: one a portrait of Marcel Duchamp (Immagini travolte dalla routa di Duchamp, 1994), another is in homage to Luis Buñuel (Quando l’occhio trema, 1989). Both quote extensively from these artists. The third ranges more widely, beginning as a direct essay in animating the serial photographs of Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, and then flashes forward to do the same to Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe silkscreens. It is this 1986 film, Piccolo Film Decomposto (A Little Decomposed Film) on which I would like to concentrate later.

Quando l'occhio trema / Paolo Gioli

Paul Virilio is a French theorist. He is well known in North America through his many short books published by the imprint Semiotexte. His first career was as a craftsman working in stained glass. He then practiced architecture and wrote his first scholarly works on architectural history including studies of 20th century military installations. Military matters remain a recurring subject of his writing. He has titled one of his books War and Cinema, his book of interviews is titled Pure War, and none of his other books is without at least a few pages on military strategy and logistics. A long phase of Virilio’s career was specialized and narrow, but it segued through May ’68 into a professorial career and he simultaneously metamorphosed into a one of the high theorists of hyper-modernity and is often compared to Jean Baudrillard. Yet, Virilio is a professing Christian and retains a long identification with French phenomenology, which puts him outside the ideological company of postmodernists. Virilio draws his leading ideas from an interrogation of modern physics. Particularly telling is the chapter of The Lost Dimension called “Morphological Irruption.”[2] It is the role that Einstein assigned to the speed of light as an upper limit that underwrites Virilio’s key concept, which is speed. Dromology–a neologism derived from the Greek for “race”–is what Virilio terms his “discipline,” the study of the effects of speed on culture, especially the speed of communications which have been approaching the speed of light itself. Widely and in most of his texts, he discusses televisual and military technologies and digital media largely in terms of their operational near-speed of light. He theorizes the effects that the approximate velocities of media have or can be expected to have on urban design, the fate of nations, geopolitics, and warfare. For Virilio, films are interesting because they represent a slower and older kind of acceleration, one that corresponds to the two world wars of the 20th century, especially the first one.

In an interview, Virilio remarks,

Cinema interested me enormously for its kinematic roots; all my work is dromological. After having treated metabolic speed, the role of the cavalry in history, the speed of the human body, the athletic body, I became interested in technological speed. It goes without saying that after relative speed (the railroad, aviation) there was inevitably absolute speed, the transition to the limit of electromagnetic waves. In fact, cinema interested me as a stage up to the point of the advent of electromagnetic speed. I was interested in cinema as “cinematisme,” that is the putting into movement of images. We are approaching the limit that is the speed of light. This is a significant historical event.[3]

Virilio also writes on perception and occasionally on art and visual culture in establishing his scheme for a theory of vision. As the quotation indicates, he regards “cinema,” or “the cinematic,” as a watershed event, a crossing of a threshold into a period that has by now been surpassed. How he comprehends cinema seems at first idiosyncratic, and in fact it stays that way.[4] Film represents what he calls the “dialectical-logical” stage in his periodization of the history of images: cinema succeeds painting (the stage he calls “formal logic”), but the medium only marks an intervening moment before the stage of “paradoxical logic” of digital media.[5] But once the initial threshold was traversed a generation ago into the appearance of digital image media, the course of the last century’s wars and their visual impact, film seems even more symptomatically intense than it did before its theoretical obsolescence. Film still plays a critical role in gathering dromological history and still serves as an important metaphor for Virilio, who conceptualizes cinema in passing but always seriously. Despite his discerning fascination for proto-cinema’s leaders and especially Marey, Virilio is not interested in film as an art and rarely comments on specific films or filmmakers. He never discusses the film avant-garde–aside from a stray remark on Warhol.

Let me introduce a further quotation about film from Virilio:

The cinema shows us what our consciousness is. Our consciousness is an effect of montage. There is no continuous consciousness, there are only compositions of consciousness. We are in the age of micro narratives… the art of the fragment recovers its autonomy.[6]

This quotation indicates that Virilio holds film to play a role in revealing forms of thinking, perception, and awareness that accompany modernity while sometimes he oversteps and claims cinema caused the kind of consciousness it parallels.

Despite the professional and intellectual incongruity between Gioli, the artisan-artist, and Virilio, the professor and theorist, their collocation is what I felt as I saw Gioli’s films for the first time in their original 16mm format. This was in the fall of 2008, when Patrick Rumble brought a set of Gioli films to Toronto. Rumble is a professor of Italian studies specializing in Italian cinema at the University of Wisconsin (Madison). He had been researching Italian experimental films and avant-garde poetry for some years and recently narrowed his focus, among the filmmakers, to Gioli, and Rumble has been carefully documenting him in the form of videotaped interviews.[7]

Some backstory: Italian cinema does not have a firm avant-garde tradition. There were some fabled Futurist films around 1916. These are lost works. A few Italian filmmakers continued through the 1930s into the 1960s but they were isolated. Then, in 1967, responding to the American avant-garde films that P. Adams Sitney was touring around Europe, Italian experimental film suddenly ballooned into a movement in Rome and Naples.[8] The movement lasted two years and was disbanded in 1969 after many of the filmmakers became politicized.[9] Experimental filmmaking still continued at an impressive pace in Italy for five years further until the introduction of video cameras and a development of a different experimental moving image, and different mode of exhibition, like sculpture or painting in a gallery.

So, Gioli came a bit late to filmmaking and missed this moment in Italian filmmaking when it seemed a movement could be sustained. Between 1967 and 1968, Gioli was in New York–and he was painting. He attended screenings of American experimental films in New York by accident and, intrigued, he returned often enough to become familiar with American avant-garde films at the height of their notoriety. Gioli observed the more sober development of structural film as well. Gioli was impressed by Michael Snow’s films particularly and might have eventually joined in, despite the fact he spoke no English. In any case, when his visa expired, he returned home. Having left Italy too soon, and having returned too late for the Italian film avant-garde’s brief coherent moment, Gioli’s subsequent involvements in the Italian art scene came through his photographic art, which he developed over the 1970s.[10] He might not have become a regular filmmaker at all were it not for Paolo Vampa. Vampa was (and is) a successful international attorney. The two met in New York at the Rizzoli bookshop and became life-long friends. Vampa became his producer, agent, and angel. Back in Italy, Gioli first tried his hand at a camera-less found footage film and a painted film, debuting with Commutations with Mutation and Traces of Traces in 1969. Vampa then provided him with a 16mm Bolex and Gioli began again. He continued, steadily but slowly, and without significant recognition, accumulating a body of films.[11] Though he never completely abandoned found-footage assembly as a genre, Gioli has concentrated on disassembling and rebuilding his film cameras and most often produces a hybrid of found footage, shot footage, and animation of plates from photo and art books. He worked diverse experiments with shutters, lens and apartures. He also built pinhole cameras and made one extended film using the technique, Filmstenopeico: Man without a Movie Camera (begun in 1972 and finalized, after several versions, in 1989).

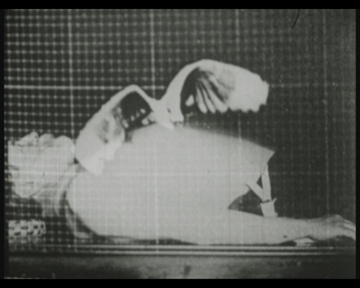

Stills from Piccolo Film Decomposto / Paolo Gioli Stills from Piccolo Film Decomposto / Paolo Gioli |

|

When I saw Gioli’s films what impressed me was the sharp contradiction between stasis and instability. His images, sometimes densely composited, rarely occupy the screen firmly. A vibration-fast movement roils them from within. Gioli is working toward something extremely immediate and yet terribly unstable and so elusive. The films rely on rapid montage, often in the form of busy superimpositions and hand-made mattes for their larger formal effects but it was the quiver of the image–always bound to its uncertain photographic registry–that seemed so unusual particularly given the craftsmanship of the films overall. His films pulsed with a rhythmic aggression against stasis and repetition, but stasis and repetition are fully characteristic. Gioli’s mastery of variations in a narrow channel of imagery is what suggests his affinity with filmmakers like Paul Sharits, but even more so with Ken Jacobs. There is surprisingly little measurable intra-frame movement here but a great deal of motion. Seldom more than a tiny action, an event in a Gioli film extends itself across the oscillatory meter of the projector’s light-pulse and is always discernible. The quick-draw label a critic wants to apply is “structural film” in one of its later European versions. This was the type of film Gioli was most drawn to in New York–and the films of Sharits, Jacobs, Tony Conrad, Peter Kubelka, and Snow form a likely formal-stylistic context in which Gioli forged himself over the 1970s. Like Kubelka and Sharits, and “flicker films” generally, Gioli composes with the 24-frames-per-second beat as a base. Also like Sharits, Gioli regards continuous motion to be a special case of more refined exploitations of the defile of static images. But, unlike Sharits’s serenely pulsed and steady violence, Gioli’s images jump and shake in the gate. This does not seem quite accurate or enough: Gioli is always dancing too close toward dissolution of the image itself at the same time he makes strategic use of film’s stutters. This is not the skeptic’s systematic disassembly of it that we see in Sharits, or the precise decomposition of it in Kubelka, or the ironic super-stabilization of it in Snow.

Long after they ceased making any films, the Italian Futurists continued to exploit cinematic metaphors in their paeans to speed, dynamism, and the machine. Bruce Elder’s recent book Harmony and Dissent reminds us how important, various, and productive the career of the cinematic metaphor was across the avant-gardes of the first decades of the 20th century.[12] But, let’s say roughly (taking one thread from Elder’s weave) that after the Italian Futurists passed their cinematic metaphor to the Russians’ assorted own Futurisms and Futuro-Constructivism, the Soviet filmmakers repaid the metaphor by putting it to practice right through the end of the 1920s. One of the most famous and direct transformations of the Futurist cinematic metaphor into film practice of a Futurist lineage was Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera (1929). This is the title that Gioli plays with in the subtitle of his most obsessive work–Filmstenopeico: Man without a Movie Camera.

At the same time as Rumble’s presentation of Gioli last fall, I was working with Paul Virilio in a seminar on the Hong Kong films of Wong Kar-wai. Wong’s cinematographer Christopher Doyle’s variable camera speeds and step printing is a much-discussed feature of these films. Aside from its percussive excitement, the device has the effect of dissolving “shots” into a mix of static and fast-blurred film frames (or “photograms”). Among the implications of Doyle’s techniques is to destabilize (and also to dramatize the instability) of the image’s temporality. Wong’s films heavily thematize the technique in counterpoint with the psychologies of his characters, especially in the diptych Chungking Express (1994) and Fallen Angels (1995). The best of Wong’s critics, Ackbar Abbas, associates Doyle’s stylistics and the director’s thematics with the complex temporalities of hypermodern urbanism attributed to Hong Kong itself. Taking his theoretical orientation from Virilio, Abbas examines how Doyle and Wong’s variable-motion step-printed cinematography torques the cinematic sign into signifying what he terms deja desperu–which Abbas explains as a reverse hallucination, a not-seeing, or as a missed rendezvous with meaning. This response to Wong’s films comes from Virilio’s The Aesthetics of Disappearance and The Lost Dimension.[13] Abbas takes a single idea, but one Virilio repeats endlessly: under conditions of “speed” the compositional certainties of time and space, horizon and figure, are subject to “disappearance.” The eye itself becomes unstable, hence the reverse hallucination: non-seeing. As we now approach vision’s disincorporation–for Virilio, “disappearance” (a multi-purpose concept for him)– arises from the divorce of vision from the eye that occurs everywhere in a culture dominated by digital speed-of-light media, like computers, television, satellite telecommunication and surveillance, etc. The corporal eye is displaced and destabilized by the “automation of vision,” and the “industrialization of vision, ” or in the book of that title, The Vision Machine.

What Abbas seized in Virilio is what he never explicates specifically but intimates often: that vision suffers this instability now, but that cinema is not the same as newer techniques, which Doyle and Wong simulate in film, though cinema already possessed a detached relation to corporeal seeing. The cinema is an early stage in what Virilio calls “prostheticized” vision. Others have also thought that about film, notably Walter Benjamin, whose model filmmaker was likely Vertov. Yet Virilio works hard and explicitly to distance himself from Benjamin’s thesis of “optical unconscious.”[14] This idea rests on the belief that cinema surpasses the eye in imaging the unseen and so the movie camera’s prosthesis is also a technical perfecting of the eye. Vertov and Jean Epstein were among the major filmmakers of the 1920s who likewise held versions of this theory and made it the foundation of their film aesthetics. In his book, Elder again reminds us, and abundantly illustrates, how such an idea of cinema might arise out of a “crisis of vision” (in his terms) and the modernist ambition for film sought–in myriad ways–its resolution.[15]

Abbas drew from Virilio a different and latent lesson: that Hong Kong, in the critical decade of the 1990s, could only be mis-seen, and represented visually, through Wong’s type of destabilized optical treatment. It had become essential for Wong to make a paradoxical seeing of the urban unseen–to make of it an unstable spectacle. Such a conception of film was not a perfection of the eye, as in Vertov and Epstein, but a confession that what the speeds our era takes away is something no man with a movie camera can catch up to much lessrestore–but this disappointment is something the filmmaker can only register expressively.

Quando l'occhio trema / Paolo Gioli

To come back to Gioli in a sudden way: Gioli made a film in 1988 called Quando L’occio trema (When the Eye Trembles). It is an ostensible homage to Luis Buñuel and Un chien Andalou (1929). Buñuel is the heretic who sprang from Jean Epstein’s experimental production team of the late-20s. Applied by his own hand in the first sequence, a straight razor brutalized the nobility of the vision–it slices a woman’s eye in fully magnified close-up–in which the Impressionist avant-garde was so invested, and that Epstein epitomized. Gioli’s film dwells intently on that Un chien Andalou opening (though much longer excerpts come from L’âge d’or, 1930). But Gioli postpones interjecting Un chien Andalou’s traumatic image of the eye in distress, and then uses only stills, until the last third of the film. Gioli’s major adjustment to Buñuel’s montage is that Gioli builds much of L’occio trema around the two-shot delay Buñuel inserted into the passage. Just before the close-up of the eye being destroyed, he performed a conventional cutaway to a full moon being transected by a wispy cloud. The graphic match of eye to moon and cloud to razor suggests an avoiding metaphor, which augments the shock of the fatally literal shot that then arrives. Gioli takes the moon and the cloud and devotes two long segments to them separately. He superimposes a rapid montage of animated round shapes over extreme close-ups of many eyes shot in variable speeds–mostly fast motion–so that their eyes wobble grotesquely side to side like frantic marbles. The overlaying animations recall Larry Jordan’s, a surprise cosmic whimsy for a Gioli film. The succeeding cloud section becomes a serious and more ambiguous symbolic slitting of the single eyes that now predominate in the montage, and this motif graduates into vertically slitting the film frame. In all this, it is not just this one woman’s eye, but also a population of eyes all trembling, shaking, vibrating, but without harm.

In the close-up shot just before his cutaway, Buñuel held the woman’s head still for a short moment, fingers of one hand wrapped over her face, the razor impending in a brutal theatrical gesture, which is what makes the cutaway such a relief. Postponing that gesture, Gioli deploys the code of portraiture, faces held within themselves, as the “domestic scenes” of L’âge d’or play under the montage.[16] Only then, the film almost over, does Gioli introduce stills that sample the beginning of Un chien Andalou. The point perhaps is that Gioli makes the eyes tremble with speed and agitated in response to faces and eyes, but, however agitated, the eyes stay inside the act of seeing.

Quando l'occhio trema / Paolo Gioli

The effect of L’occio trema is disturbing and even while gentling Bunuel’s film in making his own, Gioli is still aligned with Buñuel in dethroning the eye in theory, in displacing vision’s authority, and in imaging its unstable condition. These are not thematic or theoretical novelties. The writings of Jean-Louis Baudry, Jean-Louis Comolli and Christian Metz include the toppling of the eye from its idealist authority during the 19th century as a necessary given to understanding the very apparatus of film. Narrative film, they argue, is a replacement-compensation, an ideological apparatus built to soothe and seduce us away from grasping the actual predicament of vision in the age of vision machines. The illusionism of the movies falsely bolsters the eye in fantasy, and fetishizes its lost power in the form of “camera work” and its appearance of ubiquity covering and mastering story-worlds and eliciting imaginary identification with its inhabitants, but always finally with the camera itself. This account of film’s seduction is seen as rooted in a compensation for vision’s diminished importance as the symbol and act of idealist consciousness, and the eye’s fall is academic film theory’s fondest doctrine. The problem of the troubled eye was sketched in confirming historiographical terms by Noël Burch [17] and the historical back story to cinema has been elaborated in depth by Jonathan Crary in two books spanning the 1990s: Techniques of the Observer and Suspensions of Attention.[18] The story these writers (and the many others who joined them) tell concerns the fall of the Cartesian “camera obscura” model of disembodied subjectivity (in Crary’s characterization) before the onslaught of scientific physiologies of sight, before the separation of the senses in modern neurology, before the technological displacement of and tricks played on it, in the era of optical toys. The cinema is everywhere implied in these developments of the technologization of vision and its arrival in 1896 is almost anti-climactic, a quickly contained outcome of a radical transformation of perception resulting in mere ideological insistence that nothing has changed in the form of a reassuring narrative cinema.

Like Baudrillard, and before them both McLuhan, Virilio radicalizes Baudry, Crary and the others sight unread: the 20th century’s industrialization of vision and automatization of perception–led by military needs (i.e. sight becomes first of all, the line-of-sight in a rapid succession of aiming devices)–accelerates the divorce of the eye and vision until the latter’s technologization chases the physics of light catching up to it with their velocity of transmission. The Vision Machine at this stage dismisses the organic eye all together. The filmmaker Hollis Frampton attached to this development the date 1943. This was the year (he said) that radar was first deployed. It was also the year the art of cinema became a possibility (1943 is the year of Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon), suggesting that now that vision’s practical purpose had been disincorporated, its second career could begin. Thereafter, for Virilio, teletechnics, computers, digitality–then the first Gulf War’s “frenzy of the visible”–indicate a new history of vision without eyes. Cinema, or rather the proto-cinema of the experimenters Marey and Muybridge, is where, for Virilio, this all begins. The force of that beginning is why the cinematic can still serve Virilio as a metaphor–but now for the unstable eye.

At the start of The Vision Machine, Virilio says that the side effect of machinization is that imagination retreats as we achieve and accelerate prosthetic perception. He then turns to the slower art of filmmakers, naming Dreyer, Pick, and Hitchcock: they understood (he says) that we comprehend a film through what we remember not what we perceive moment to moment.[19] Eisenstein theorized that film works by the superimposition of one photogram upon another: the viewer synthesizes them and the “shot” is fused dialectically into motion.[20] The speed of cinema still privileges, for it depends on, the stability of the surface of the eye to register the defile of the image as motion in time. This requires human capacities of eye-memory to hold what we call a shot together as a visual entity. The eye is involved in a gathering process; this is of a piece with Virilio’s remark quoted before–“no continuous consciousness, there are only compositions of consciousness.” Virilio adds, when speaking of cinema elsewhere, that there is no such thing as fixed sight. Eye movements are incessant and unconscious and also constant and conscious. The visual field is an undifferentiated whole and then we see and we compose. Using a metaphor, he writes, “Sight comes from a long way off and comes out of a past toward the object of perception.” The cinema behaves in a manner close to our familiar knowing and seeing because cinema takes time, however short in duration, to let our perception process it. In 1918, 24 frames a second seemed fast, but when comparing it to the speed at which pixels flash, we are reminded that film really moves at the rate of a sewing machine. The change occurs when vision technologies cross into digital vision machines operating at an electromagnetic speed. They open and cede no time to the eye operating as they do nearer the speed of light, and they permit no space of seeing “from a long way off.”

* * *

Now, let me make three obvious observations. First, Virilio’s remarks of eye movement are uncannily close to Stan Brakhage’s account of the eye and film in his Metaphors on Vision. As another book by Elder explains at length, Brakhage’s films systematically include the eye’s tremble and the beat of vision-time. It is this insight, I think, too, that informs Gioli’s eye tremble in his Buñuel homage, and in most of his films, Gioli modifies the cruelty of blindness into a portrait of the eye’s accelerant action already there in cinema. Second obvious remark: Snow’s films graph the action of “sight coming from a long way off”–as an index of time–in Wavelength (1967) literally across the deep space of a New York loft–to arrive, after a complex series of “compositions of consciousness” at its final object, a still and deeply ironic photograph of waves pinned between two windows. Finally, and also obvious, is this: cinema has two speeds. Playing on either cinematic speed, a filmmaker can unsteady the image as ordinarily seen and make the eye’s perception unstable and this can be a revelation. The first is projector speed and Gioli composes with this always as his base: 24 frames per second. He has spent a large part of his career tinkering with cameras’ shutter devices and speeds–in finding ways to rejig that speed, and the counterpointed rhythms of his images’ shutter and stutter attests to this speed. Speed two: less often remarked is the speed of light in cinema. This speed may be claimed to be qualified in its registry, but not changed, by film stock chemistry and lenses, by how “fast” the celluloid surface receives the light, registered by qualities like contrast and brightness.

Virilio insists cinema was made possible by the achievement of “instantaneous photography.” Why insist on this fact? The communication consequences of speed-of-light digital and televisual media loom very large for him. Photographic instantaneity is not that fast. For the same reason, Virilio is interested to see cinema as the slower art built of sense memory that was engineered around the first era of mechanized war. Light speed is already entailed in the dialectical art of the photogram “frame” that passes into a sudden past: its inscription is an act of light, its witness capacity depending on it. The film image and the remembering eye that grasps it in projection and gathers it makes it stable. It was Marey’s and Muybridge’s epochal preoccupation to make that perceived stability an issue. And this is why cinema is the threshold between the past (of painting) and the impending future of technologized eye-less vision for Virilio. This is why, in his extremely rare citing of an avant-garde filmmaker, Virilio notes the irony of Andy Warhol’s early silent movies: that in the era when televisual speed rose to prominence (in McLuhan’s home decade, the 1960s), Warhol made the slowest movies he could: Sleep (1963), Eat (1964), Haircut (1963), Kiss (1963), Blow Job (1964), Empire (1964). Virilio does not mention that Warhol shot these films at 24 fps but showed them at 16 fps. His inertial cinema makes cinema’s first speed a delicious decelerated agony–and a riposte. We can almost count the immobile frames.

Gioli is interested in light speed, too. This is especially apparent in his pinhole camera work. The pinhole camera does not move the film at all. The filmstrip is laid vertically in his design and light-sealed on a board that is punctured at short intervals. The whole strip is exposed in a single gesture without a lens, through the tiny holes. The image is just the impress of light at light speed along a series of frames. The technique removes the 24 fps speed from the cinematic equation and leaves the results of light speed, unaided (or impeded) by a lens. The pinhole camera is an old type of still camera that Gioli turned into a cinematic device. The 24 fps comes back in projection, of course, but the moving images appear to dance and are accompanied by a luminous tremble of pure light in Filmstenopeico–the slight off-register shake between the pinhole apertures, violent flares of accidental light, manifesting as veiled witnesses to film’s light speed. The paradox is that when Gioli removes the lens–the light-gatherer and regulator of film’s light speeds in the technical sense–the cinema’s light speed has this more sharply felt impact. Although his pinhole film serves almost as a demonstration of Virilio’s super-modern thesis, there is a deeply antiquarian side of Gioli in all this. The pinhole camera is an old device, and in homage to Fox Talbot (whose first window photographs the filmmaker elsewhere animates), Filmstenopeico begins with a long section of shots of and through windows and it is here that direct light makes its appearance. The pinhole device was born of artists preoccupied with light, not with machine time, a concern that Europeans trace to the Renaissance. Gioli comes to his insight via cinema, and comes to create his films, through ancient and very Italian reflections. They are witness, too, to modernity’s unstable eye–but here in the presence of an ancient light–or, rather, light made ancient by Gioli’s devising.

To finish, I would like to offer one final remark of Virilio’s. He is speaking of Marey in The Aesthetics of Disappearance.

Emphasizing motion more than form is, first of all, to change the roles of day and light. Here also Marey is informative. With him light is no longer the sun’s “lighting up the stable masses of assembled volumes whose shadows alone are in movement.” Marey gives light instead another role: he makes it leading lady in the chrono-photographic universe: if he observes the movement of a liquid it’s due to the artifice of shine pastilles in suspension: for animal movement he uses little metallicized strips etc.

With him the effects of the real becomes that the readiness of a luminous emission, what is given to see is due to the phenomenon of acceleration and deceleration in every respect identifiable with intensities of light. He treats light like a shadow of time.[21]

This is a poetic passage for so unpretty a writer as Virilio. Marey made still images only, using his invention, the chronophotographic gun, which superimposes images of motion slightly off-register to produce evenly spaced superimpositions over the blur of lights that index different body positions.[22] It is an advanced kin to the pinhole camera in pursuit of fixing instantaneous light into its real shapes. Gioli sees himself in that lineage, and he is also consciously, or not, a filmmaker who puts himself back at Virilio’s threshold, that is, by making a film where light-time plays too. In 1985, during the interval between two later versions of Filmstenopeico (1981/1989) Gioli made Piccolo Film Decomposto, which deploys many images taken from Marey and from Muybridge.

The film begins in stasis with an archival photograph of a prone man, perhaps a dead man. Readily suggestive of some sort of flight, Marey images are superimposed, then a montage of Muybridge images; then two erotic-oneric scenes, shot for the film but shaded by mise-en-scène to seem much older, begin. For some considerable time after this, the film seems simply like skilled animations of Marey’s and Muybridge’s plates. Yet they were artists of the “interval”–both worked with motion using still but serial photography–and in Gioli’s reanimation, intervals between “frames” (as Virilio argues) become key to the dialectic of “presence,” something Gioli soon renders apparent by a combination of repetition of short fragments and subtly managed variations of meters for each pass at a Muybridge series. It was Marey’s thesis that his work was wholly analytical because the unaided eye cannot see the truth–the temporal interval is critical because nature occludes it while photo-mechanization permits it to become his subject matter–which was obsessive for Marey and Muybridge both. Muybridge’s subject mater belongs to the center of the sign culture of Western visual art: the naked human body stood, lain, or walking on a ground. For Marey, animals and birds do as well as humans: the body in movement is more often body in flight. In their work, subject matter strained at the then-new medium, still photography, nudging it towards cinema, but the collision between stasis and illusion of motion made manifest that they were not the same order of image. Virilio’s dialectical logic of the frame is rendered visible.

Gioli’s film is about this: a restaging that makes it manifest. There is also a direct film genealogy here, accented by Gioli interjecting the whole of Edison’s Fred Ott’s Sneeze (1894) followed by an Italian primitive of similar vintage and probably of a man singing. These very early films, both of which are single shot close-ups, begin a modulation of the film in other terms of our sign culture: from the full body nude to the close portrait. The portrait is a different measure against which to experience the novelty of speed: a portrait proffers its look directed to my look (that status of the classic eye to my eye) in a stasis of positioning (I must stand somewhere before a Rembrandt).

Stills from Piccolo Film Decomposto / Paolo Gioli Stills from Piccolo Film Decomposto / Paolo Gioli |

|

Then, the mild shock of Andy Warhol’s appearance, the pop portraitist of his time: For Gioli, Warhol is the end of the Marey-Muybridge chain of events but he does not allude to Warhol’s films. Instead, he makes film of the Warhol who is also portraitist. A Warhol “contact sheet” of stills of his own picture becomes a Muybridge-Marey-like portrait–Warhol twists his head into a blur. Then, Gioli does the same with Marilyn Monroe, using one of Warhol’s serial silk screens of her image like a contact sheet. What registered as hot spots and glare in the original press photo Warhol renders in mis-registered areas of ink: the flare of light that initially produced exaggerated lips, fair hair, and cheeks becomes distorted by offset ink in the shape and rough edges of the photoflash. Warhol recognized the effect and improvised upon it in his distribution of colors. Draining these to grays, Gioli restores the images to an almost-original condition of photographs–almost, but he retains the shapes and modulations of darkness that Warhol’s splashy silkscreening produced–that is, Warhol’s accepted rendering of photo lights. In the collaged setting of Marey and Muybridge animations, Gioli reaches back to the “leading lady in the chrono-photographic universe” to her true role in Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn, leading lady in the Warhol gallery, the job of light’s stand in. Gioli interprets Warhol here by giving him a genealogy in the arche-history of the cinematic interval–whose fathers are Marey and Muybridge. And in doing so, Gioli places himself within his elective history as a filmmaker.

1. Suddenly, this is changing. The Winter 2009 issue of Cineaction included a critical essay by Patrick Rumble, “Free Films Made Freely: Paolo Gioli and Experimental Filmmaking in Italy.” The Centro Sperimentali Di Cinematografia recently published a lavish bilingual catalogue-anthology, Imprint Cinema Paolo Gioli un cinema dell’ impronta, edited by Sergio Toffetti and Annamaria Licciarddello (Rome 2009). Contributors include Dominique Païni, Elena Volpato, Bruno Di Marino, David Bordwell, and Keith Sanborn. There is also an extensive interview with the artist and Gioli’s annotations of all his films to 2003. The book is richly illustrated with stills, his photographs and paintings and includes a PAL-format DVD containing six of his films, complementing the recent Rarovideo two-disc collection Film di Paolo Gioli.

2. Paul Virilio, The Lost Dimension (New York: Semiotexte, 1991), pp. 29-68.

3. “`Is the author dead?’ An Interview with Paul Virilio,” The Virilio Reader, edited by James Der Derian (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), pp. 16-17.

4. There have been some attempts to comprehend Virilio’s remarks on cinema in terms of a more conventional film theory. The best and most adventurous of these is by the late Anne Frieberg. See her The Virtual Window: from Alberti to Micrsoft (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006), pp. 182-189.

5. Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994).

6. Paul Virilio and Sylvere Lotringer, Pure War (New York: Semiotext, 1983), p. 41.

7. Rumble’s “Free Films Made Freely” is the first publication of his to discuss Gioli.

8. See Rumble, who provides a careful and succinct account of the Cooperative Cinema Independepente (CCI), who was formed in 1967, and the setting up of the Filmstudio theater in Rome that same year. It is Rumble who attributes this development to the New York Co-op model and the influence of Jonas Mekas and Sitney.

9. See Rumble, “Free Films,” for a succinct account of events.

10. Recent research by Justine Iaboni into Gioli’s relationship with the Italian filmmakers indicates that he was later marginalized in retrospect, cast as a visual artist who made some films. This may account further for the obscurity of his films even after he had achieved a reputation as a photo-artist. However, it should be kept in mind that experimental films rarely arise from obscurity even in relatively supportive circumstances (i.e. Vienna, Berlin, New York). Italy, wherein most artist-filmmakers drifted toward video, has never been a launch pad for experimental films. (Iaboni’s study, “Immagine travolte routa di Paulo Gioli” was conducted in the MA program of the Cinema Studies Institute, University of Toronto, 2009).

11. His filmography continues in 1969 with Trace di Trace; Gioli made two films in 1970 and six in 1972, then settled into a slow rhythm of one or two films a year to the present.

12. R. Bruce Elder, Harmony and Dissent: Film and Avant-Garde Art Movements in the Early Twentieth Century (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2008).

13. Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1997); also see Abbas’s “The Erotics of Disappointment,” in Won Kar-wai, edited by Jean-Marc Lalanne, David Martinez, Ackbar Abbas, and Jimmy Ngai (Paris: Editions Dis Voir, 1997), pp. 39-81.

14. Benjamin’s widely cited notion of the “optical unconscious” appears in his essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Virilio’s critical remarks on Benjamin appear in several places, the most extended appear in The Lost Dimension, pp. 69-85.

15. Elder, Harmony and Dissent, p. x. Elder’s discussion of Constructivism, Eisenstein, and Vertov occupies almost a hundred and fifty pages of his book, pp. 279-438, but see especially pp. 331-345.

16. By the “domestic scenes” I mean the short episode during which the heroine rises from her couch and has a discussion with her mother before going to her bedroom when she encounters a cow.

17. See the essays gathered in Burch’s Life to those Shadows by editor Ben Brewster (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), especially “Charles Baudelaire vs Dr. Frankenstein.”

18. Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992); Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999).

19. Virilio, The Vision Machine, pp. 3-4; also see The Virilio Reader, p. 12.

20. S.M. Eisenstein, Film Form, edited by Jay Leyda (New York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1949), p. 14. Eisenstein writes, “For, in fact, each sequential element is perceived not next to the other but on top of the other. For the idea (or sensation) of movement arises from the process of superimposing on the retained impression of the object’s first position, a newly visible further position of the object.”

21. Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance (New York: Semiotexte, 1991), pp. 18-19. His italics.

22. To amplify light’s registration, Marey sometimes dressed his subjects in black and attached light-reflective “strips” and the photographs produced became a detailed graph of motion. For discussion of Marey’s methods, see Marta Braun, Picturing Time: the World of Etienne-Jules Marey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), Chapter 3, pp. 150-199.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bart Testa teaches at the Cinema Studies Institute, Innis College. He has published two books on experimental films, Back and Forth: Early Cinema and the Avant-Garde (1993) and Spirit in the Landscape (1989). He also co-edited the anthology Pier Paolo Pasolini in Contemporary Perspectives (1994) with Patrick Rumble. His critical essay on the Vancouver Island films of Stan Brakhage appeared in The Canadian Journal of Film Studies.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Counter-Archive