Interview with Jim Hubbard

By Joel Schlemowitz

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

I first encountered the work of Jim Hubbard back in the days when he was screening his recently completed film, Two Marches (1991), contrasting the two Gay Pride marches taking place before and during the AIDS crisis. The film’s formal structure of two successive chapters might recommend it as an example of short film construction. There is elegance in its dyadic framework. But it is a more complex work than just this, combining elements of personal cinema, documentary, experimental technique and sensibility through its use of hand-processed, solarized images, and political filmmaking.

I’ve always had an interest films that find pathways of escape from the constrictions of one type of filmmaking or another. The typical film festival entry form instructs the prospective entrant to check one box, and one box only: Narrative. Documentary. Experimental. But for Hubbard’s work multiple checkboxes often seem like they ought to be ticked, or perhaps an additional choice should simply be: Narrative. Documentary. Experimental. Jim Hubbard.

The occasion of a three-screening retrospective of Jim’s work at The Film-Makers’ Cooperative [March 4, April 1, and May 6, 2016] presented an opportunity to conduct this interview on the heels of a comprehensive viewing of his films. I was also curious about the color hand-processing prevalent in many of the films as well as the relationship between the shorter works and the feature documentary United in Anger (2012).

* * *

Joel Schlemowitz: I’d like to tak about the three screenings you did at The Film-Makers’ Cooperative. We could start by talking about Homosexual Desire in Minnesota (1981-85). How long had it been since you’d last shown that film?

Jim Hubbard: I think 2001. There just aren’t very many places that can show Super 8. Also there are a limited number of places that are interested in showing a 69-minute Super 8 film, so it’s never shown very often, and I don’t have a decent digital transfer of it. Perhaps if I did have a transfer of it I would be able to show it in other places. I was a young filmmaker when I started it, and I was trying to figure out how to make films, and also trying to figure out what life was about. So the way to do that was to film it. In fact, that’s something that has continued, I like to say that in a certain way I can only begin to understand the world through the viewfinder of a camera, and never fully understand it until I’m editing it. I don’t remember when I decided that I was making a long film that was going to be structured in a certain way; probably very early in the process. I’d started filming an awful lot because I was buying these expired Super 8 cartridges and as I remember they were about 50 cents a reel. I don’t imagine the cost is the same now. So I had all this footage and I kind of got overwhelmed.

Schlemowitz: You were also hand-processing all this film, which brings us to another topic. It’s one thing to want to take a Super 8 camera and go out and film, but then I’m curious about how the hand-processing factors into this too.

Hubbard: That happened when I met Roger Jacoby. We met in San Francisco in 1977 at James Broughton’s 64th birthday party. When I saw his films it was a complete revelation to me. His films are like moving abstract expressionist paintings: the hand-processing changed the imagery of the film in a way that I don’t necessarily do in my films. Often in his films you can’t tell that there’s a photographic image – a figurative image – while in my films it’s usually the case that you can tell there are figures and objects. But it was very exciting to me, and I loved just doing hand-processing, and loved the hands-on aspect, and learning the rhythm to wind the film into the little torture device, the Superior Bulk Film processing tank, and discovering how to work with the chemicals.

The first time I did it I was still a student at the San Francisco Art Institute. I just went into the photography lab and processed the Super 8. At the time I didn’t know how much light you needed for re-exposure to reverse the footage so I used to take the tank outside and hold it up to the sun, like some ritual. I was also taking a course from Broughton called Androgyny so that kind of spiritual stuff was also in the air. But in order to dry the film I had to put it in one of those cabinets that are set up for the photographers with their six-foot lengths of film, and I had these 50-foot lengths and had to wind it – people just thought I was doing something crazy. You could see they looked at me through the corners of their eyes and kept their distance. But the process was really exciting to me and I continued doing it, even to the point where I was processing Kodachrome by myself. I could do it because I would beg the chemistry off of this lab. By that time I was living in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and just happened to call up this lab and talked to this young woman who said, “Sure! Come on down!” She didn’t know what she was getting herself into either. So I brought the seven one-gallon jugs that she asked me to bring and siphoned the chemistry from these 300-gallon drums. It got all over the place and I still remember mopping it up. But she let me come back twice. I got to process about 30 reels all told.

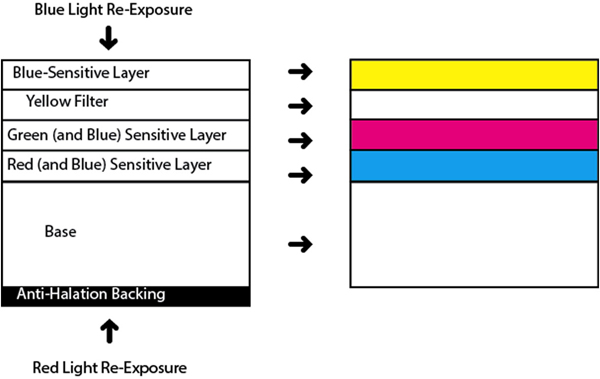

Schlemowitz: I’m curious about what that process is like. Don’t you have to do something like shine red light through one side and blue light through the other?

Hubbard: Kodachrome film has basically three layers. The top layer will eventually be yellow, the middle layer will be magenta, and the bottom layer cyan. You have to process one layer at a time and the developer also has the color coupler. In the presence of exposed silver, they bond and form a dye. I don’t really remember the order you do it in.

Schlemowitz: I’m more interested in hearing about how the whole process worked rather than in the order of the steps.

Hubbard: The way Kodachrome works is that you first process the negative as black and white, then you have to process each of the layers separately because the color couplers are in the developer and not imbedded in the layer (as in Ektachrome). In normal processing, you would first re-expose the bottom layer with red light through the base, then re-expose the top layer using blue light, finally developing the middle layer, which has chemical re-exposure agents in it. Since I was using a Super 8 tank where the film was wound on a reel, I couldn’t expose through the top or the bottom, but only all at once. I solved this problem, by using a green light and a red light because only one layer is sensitive to each of those colors. Then I could develop either the yellow developer or the blue developer. I could mix and match the lights and the developers, thus changing the color balance, but the magenta developer would always have to go last.

But it was the change in the color balance that I was most interested in and as you can see in Homosexual Desire in Minnesota, it allows a huge variation in color. In fact, I edited the first Gay Pride sequence as a kind of rainbow with blue-dominated shots, then yellow shots, then red shots.

(For a fuller explanation of Kodachrome processing, see photo-utopia.blogspot.com/2008/12/how-it-works-kodachrome.html)

Schlemowitz: I’m curious as well about the interrelation in your films between the technical experimentation, the work as diaristic, the work as documentary, maybe also as political filmmaking.

Hubbard: Let’s start with the documentary and the political, which often gets lost. I’m a very political person. I guess I think of myself as a dedicated leftist who wants to change the world. Bernie Sanders is too far to the right for me! You want to talk about political revolution, let’s do this for real. But the motivation for filming demonstrations is also that people are focused on something else, so that they don’t notice the camera. They don’t behave in that way when they are conscious of a camera being around. Occasionally in my films you’ll see people wave at the camera, but I think I keep that in order to call attention to the other behavior, the non-camera-oriented behavior. I’m interested in how people move and how they position themselves towards each other, and gesture and behave towards each other.

Schlemowitz: But also in terms of the films also having a personal, diaristic aspect, I find it interesting how a film like Homosexual Desire in Minnesota modulates between the diaristic film tradition, documentary, and political filmmaking. In making the film was that something you were doing from the outset? Was it something you were looking to have come across to the audience in this way?

Hubbard: In terms of the diaristic aspect, I wasn’t filming everyday but I was interested in filming my everyday life. I was also filming people for whom being filmed was a very sensitive issue. When gay people demonstrated they were very self-consciously being in the public eye, so the camera wasn’t an intrusion the way it was at certain other times. There’s the party scene in the section about Roger where I had to be very discreet about filming. I was in this chair and was off to the side and was very quiet about it. And the beach scene at the end of the film I just held the camera down, parallel to the ground so it looked as if I wasn’t filming.

It’s about ordinary life, it’s episodic, and there is no narrative arc. Like the section on Lars, the handsome diffident young man lying on the sand next to the beautiful lake with a Mozart violin concerto on the soundtrack. He’s a guy I had an affair with, I was insanely in love with him, and it was a huge disaster. It’s actually the last time we saw each other and I just forced my camera on him. The section of the film with Donald, which is the only silent section, and is a portrait of a friend who was the first guy I had an affair with after I broke up with Roger. I originally had music playing, but I was never satisfied with it and finally removed the sound entirely. That section resonated with the audience in a way that it never has before. Since it’s a silent section, it was a bit of a surprise that the audience felt this way. But Donald was feisty, he took the camera and he filmed me, which I was not happy about. It was sort of a date to film, and then suddenly he had to go see his daughter, who was a baby. So she got in the film. She’s now in her 30s.

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

Schlemowitz: Can we talk about the use of music in the films? Especially with Two Marches there are these abrupt endings of the music at some mid-point, and then a period of silence.

Hubbard: In Homosexual Desire in Minnesota I was clearly influenced by Kenneth Anger. But I was also trying to use the music that was around at the time in order to convey the emotion that existed at that time. It’s something I’m usually against.

Schlemowitz: How do you mean?

Hubbard: Well, the big problem with music in film is that it is so often used manipulatively. That’s the whole idea of the use of music in Hollywood movies; to force you to have a particular emotion at a particular time. I generally am against that, but in the case of Homosexual Desire in Minnesota I did want to convey some of the emotion. The people in the film watching the Bette Midler drag queen performance were genuinely moved, they really were crying at hearing those songs, so I felt it was important to convey that.

In Two Marches the sound is about its being taken away, that’s the reason for the abrupt endings, because it’s about AIDS, it’s about how people just disappear. Suddenly they’re gone, they’re dead, and I wanted to use the music to underline that. All the music in Two Marches is music that was performed at the march itself. Tom Robinson sang “Glad to be Gay,” and Holy Near sang “Over the Rainbow.” In fact, the footage of the show is of the sign-language interpreter during that song. And then there’s the Michael Callen song “Living in Wartime” also. But yes, the abruptness of the ending was very deliberate.

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

Schlemowitz: Then there’s that long period of silence at the end while we’re viewing the AIDS Quilt.

Hubbard: Yes, it’s supposed to feel awkward, to feel like something’s missing. I think the music conveys a certain emotion while you’re listening to it, and then you have it taken away from you.

Schlemowitz: Interesting in terms of the silence – rather than the music – being used to convey an emotion.

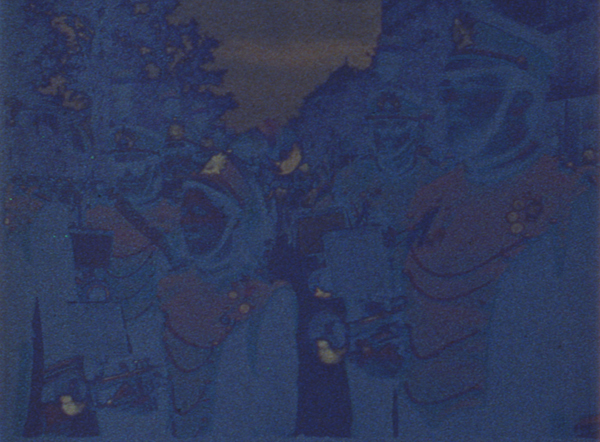

Hubbard: Also, with Two Marches, there’s a certain abstraction when the film gets solarized: to me it feels like a literalization of what it feels like to be on the Quilt, like you’re surrounded by ghosts. In the march sequences, where it cuts between realistic footage and solarized footage, it’s a way of saying “These people could be dead.”

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

Two Marches / Jim Hubbard

Schlemowitz: A technical question about how it was done in that sequence: Did you have an internegative made?

Hubbard: In 1984 I got this little processing machine and started working with it. It was originally designed to process black-and-white film and took a reasonable amount of time to process a single roll. But if you wanted to do Ektachrome, like ECO or EF, they’re very soft films so they have to be processed at cold temperatures, like 68 degrees, and it takes an incredibly long time. So it was frustrating to do it. There are several things you can do to solve this: you can add a hardener, but this will only allow you to raise the temperature a little bit. Sometimes I would process film and the temperature was too hot and the emulsion would just come off and create all these crazy patterns.

At some point I discovered VNF film stock. VNF, which stands for Video News Film, was designed for television stations. The color temperature of the photographic image is very blue-looking, because blue looks much better on television, at least with analog television in the 1970s. It’s a pre-hardened film stock, so you can process it at high temperatures. It also doesn’t have an anti-halation backing, which was great because with the processing machine this had been a nightmare, it was incredibly messy, and it doesn’t come off by itself, you have to sit there with your fingers and a sponge and wipe it off. So VNF was so much easier to process. A lot of Elegy in the Streets (1989) is VNF. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but it’s a very blue film. It’s a serious subject, so blue works very well.

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

It eventually got increasingly difficult to get reversal prints, and so for Two Marches and Elegy in the Streets I made internegatives. But with The Dance (1992) I thought, “Why do it this way? Why not just process the VNF as negative?” So instead of it being very blue the film was very orange. But I liked that a lot, and it certainly made my life easier. I could do about 800 feet of processing in about 12 hours.

Schlemowitz: Let’s talk more about Elegy in the Streets, another film where it feels there is a confluence between experimental/personal/documentary, and a film that might relate in an interesting way to United in Anger.

Hubbard: It’s clearly – “predecessor” is not the right word – although a lot of the themes that are in Elegy in the Streets are in United in Anger. The personal themes are not – or not there in the same way.

When AIDS first appeared I wanted to make a film about it, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it, because what was happening at that point – at least in terms of media – was that the news channels would go and take their cameras and they’d go into people’s hospital rooms and literally film them on their deathbeds, literally in their worst possible moment. Or when they would interview people they would backlight them so they would be in silhouette. It was reinforcing and enforcing the stigma around AIDS, because this was even before HIV had been discovered. I wanted to do something else, something that would analyze the political situation, and that showed the personal situation in a more humane way. That was really difficult because people don’t like to be filmed in those moments.

I began filming a friend of mine named Billy Burke, but it didn’t last very long because he didn’t want the camera in his face all the time. There’s only one shot in Elegy in the Streets from that part of the making of the film. It’s the shot of the back wall of a tenement. He lived on 5th Street and had a garden in his backyard, so I filmed the morning glory going up the side of the building. I kept trying to film him, and not very successfully, but then two things happened: one was that Roger Jacoby was diagnosed with AIDS in August of 1984 and died in February 1985. He wanted to be filmed, so I filmed him as much as I could, although he wasn’t living in New York, so it was when I visited. The last bit of his life he lived with his mother upstate so I would visit there. I filmed that and then inherited his outtakes; he would film himself a lot so I had all this footage. The second thing that happened was that ACT UP suddenly appeared and there was this very graphic, very filmic, very public response to the AIDS crisis. So I could film that, and this footage became very diaristic, too. There were so many demonstrations that I would be doing it all the time, demonstrating and also filming. So it was those two elements.

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

Elegy in the Streets / Jim Hubbard

An elegy is a poem that has certain characteristics. The basic structure is that it takes a death that is personal to the author and uses it to make a larger political statement, which is exactly what Elegy in the Street does. But there are other things that are part of an elegy: a catalog of flowers, a procession of mourners, a visit to the underworld, and a swain character. There really isn’t a swain character in the film, but Roger sort of functions that way, and the location in the film of Shea Stadium [in Queens, NY] becomes the meadow at the end of the elegy. But there are all those flowers in an elegy, and there is something poignant and beautiful about how they last for only a short time, so an obvious relationship to AIDS, and the procession of mourners are the ACT UP demonstrators, and the visit to the underworld is the sequence in negative black-and-white, with The River Styx and everything, which literally is a creek in Minnesota, but it looks like The River Styx to me.

Schlemowitz: Was it mostly you filming things that were happening at the time, or did you have these elegiac concepts in mind? Was it a compulsion to get footage of these things and the structure of the piece came later?

Hubbard: Yes and no. The way I film is that I have a theme, I have a subject. I had wanted to make a film about AIDS. In the beginning I didn’t exactly know what that was going to be, so I did very obsessively film and film and film. Then at a certain point I had this feeling: “Oh, I have a critical mass of footage now. Let me edit and make sense of this.” It’s only in the editing process that it starts to make sense, when it gains that structure and meaning. As I said before, filmmaking is a way of making sense of the world to me, but it’s in the editing process, looking at that footage over and over and over again to see, “Oh! That means something.” This shot means something in relation to another shot, so I can start putting it together in that way. That’s how I discover meaning and the structure. And I almost never go back to film more. For me the filming and the editing processes are very much separate.

United in Anger / Jim Hubbard

United in Anger / Jim Hubbard

Schlemowitz: I’d like to talk a bit about United in Anger. I’d asked you at the screening of your work at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative how the previous short films you’d made had informed United in Anger. I guess Elegy in the Streets is the film that most overlaps in subject?

Hubbard: Yes. “Prototype” is not exactly the right word, because when I made Elegy in the Streets I thought it was my definitive statement on the subject. A number of the demonstrations that are in Elegy in the Streets are also in United in Anger. United in Anger encompasses a slightly different time-period. Elegy in the Streets, discounting the flashbacks of Roger from the 1970s, was basically filmed from 1983 to 1988. I can’t remember exactly when I stopped filming, but it was finished in late 1989. The film isn’t quite in chronological order. United in Anger starts in 1987 and basically goes through 1993, with the addition of 1997 and 2007 marches that are included.

Schlemowitz: More specifically in terms of these being two films about political protests in reaction to the AIDS crisis, did Elegy in the Streets inform how you were going to approach United in Anger, or do you see them as two very separate films that happen to have an overlap of subject matter?

Hubbard: I don’t think so. One of the things that makes United in Anger very different than most AIDS documentaries is that it is from a personal point-of-view. What I adopted in this approach was to make the film from ACT UP’s point-of-view. But of course it’s my version of ACT UP’s point of view, and you can see the beginning of that in Elegy in the Streets.

United in Anger / Jim Hubbard

United in Anger / Jim Hubbard

United in Anger is made up mostly of other people’s footage shot in video while most of my other projects have been hand-processed 16mm film. I did get to have a good digital transfer made of Elegy in the Streets in order to put a couple of shots from it into United in Anger. The problem of making the film was very different; in Elegy in the Streets it’s all my footage, it’s my personal point-of-view. How do you do that when you’re using other people’s footage? You have to edit it in a particular sort of way, and I wanted it to literally be a film from the activist’s point-of-view. So the shots are all at eye level; I’ve tried to put you right in the middle of the demonstration. It’s not shot like TV news footage, where they stand off to the side.

One of the things I’m most interested in is people’s faces. The way most people shoot demonstrations is they try to convey the mass of humanity. I do the opposite: I try to find the individuality in that mass. So I’m constantly shooting faces and the crowd moves and then suddenly someone’s face comes into the center of the screen and you feel as if you get to know something about that person. I think it’s a very interesting filmic phenomenon. You are seeing a crowd of people streaming by and suddenly one face with a very particular expression or someone doing a very specific action pops out of the crowd and even though it’s only for a few frames it makes a very strong impression.

Here’s a good example: a group of three guys walk by with their arms around each other. The guy on the left gives a peck on the cheek to the guy in the middle, who turns and kisses the guy on the right. It takes longer to describe than to see, but it’s a wonderful expression of affection, solidarity, and lighthardedness in the midst of a very serious demonstration. Another example is the crowd going by and a woman with a very worried look on her face fills the screen. That highlights the individual emotions that are continuously occurring in a demonstration, but also signals the potential danger that is always there. I think it’s related to Eisenstein’s editing methods. Think of how he cuts to certain faces in the midst of the Odessa Steps sequence. In my case, it’s not an abrupt interruption so much as something that flows from the composition and movement on the screen.

Another aspect in the process of making United in Anger that was very different for me is that for the first time I was working with an editor. I had done a little piece in video with an editor because I didn’t know how to edit video, but in that case I just said, “This shot: start here, end there. Next shot: start here, end here.” Ali Cotterill, the editor, and I talked, and then she would go home to Brooklyn and edit the footage and show it to me. We had matched hard drives, so all she had to do was send me the Final Cut session file and I could see what she did.

Schlemowitz: Very nice!

Hubbard: Yes, it was very nice. So I could watch it and then the next day say, “No, you need this. This doesn’t work.” Whatever my critique of it was. She did try to reproduce my editing style, but she had a huge influence on it as well, because the first cut of United in Anger was all demonstration footage. I tried to convey the entire story using archival material. The reason to bring Ali on was that she knew Final Cut much better than I did, and something that she could do in ten minutes would take me two days to do. So there’s that. Certainly something that facilitates making an hour and a half long film. But also, I needed someone who didn’t live through that period of time, who would know what was necessary for someone else who didn’t live through it to understand what was going on. So it was Ali who edited all the explanatory interview footage. She’d say, “Okay, we need someone to explain why they’re doing this demonstration.” And I’d say, “Look at this, and this, and this, and this.” She’d look at everything and then pick out material for us to work on together.

But United in Anger is also a chronology and analysis of ACT UP’s actions. The graphics of the timelines were there to show that much more was happening than could be fit into any one film. The timelines are the half dozen or so short sections that occur periodically throughout the film that literally show a timeline with a date and intercut several shots from a number of demonstrations that happened within a short period of time. These were created on a computer, but they are graphically treated to allude to 1980s video graphics. There’s a certain irony to this. When we first started talking about this both Ali and Mike Millspaugh, who was the graphic designer, insisted that the timelines should not look like 80s video graphics, but they ended up doing just that. I loved that because in a way this mimicked the process of how many AIDS activist videos were made in the 1980s and 90s. They were made collectively and different small groups of people took responsibility for different sections, so often some sections looked very different from the rest of the tape.

I wanted the film to also serve as a blueprint for how to do effective grassroots political organizing, including things like civil disobedience training, the section about affinity groups, and people talking about what makes ACT UP unique, such as the posters and artwork. The section on the AIDS activist video-makers is near the beginning of the film because I wanted people to know what made the film possible. The section about the posters is also near the beginning of the film because I wanted to tell people what to look for when they’re seeing the footage of the demonstrations. Those are all things in United in Anger that are not in Elegy in the Streets. But what’s in Elegy in the Streets is the sense that for every person out there on the streets in the protests there is a very personal underlying reason, whether it’s because he’s HIV infected, or because a lover or a friend has AIDS and died. Roger stands in for those people in Elegy in the Streets. Whatever emotion that is being expressed is more directly conveyed in United in Anger.

Schlemowitz: It’s interesting what you say about the film showing the work of political activism, rather than the part that’s just displayed in public for the camera.

Hubbard: Yes! Because I think it’s really important to convey that it’s actual work. At the screening at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative there were some people from ACT UP in the audience, and there’s a certain amount of awkwardness because a film has to have a beginning and an end. Yet ACT UP still continues. It’s not nearly as big as it was in the late 1980s and early 1990s and the people in it now are really sensitive about this.

So I was very glad that those guys weren’t, and that’s why the 1990s and 2000s marches are in the film, to acknowledge the fact that ACT UP still exists even if the film – for the purposes of making a film – has a narrative arc that beings in 1987 and more or less ends in 1993.

Schlemowitz: The classic situation is the documentary where they go out and shoot and edit, but in the meantime more has happened, and so they go out and shoot some more, but then life keeps continuing and at a certain point one just needs to say the film ends here.

Hubbard: With Elegy in the Streets for some reason I felt that by 1988 I had a critical mass of footage and should start editing, even though it ends in the middle of things; there’s certainly no resolution to that film. I’m not even sure I thought about the film that way, but it could have gone on for several more years at the very least. It’s interesting, after 25 years I don’t remember what prompted me to stop filming.

At a certain point I also wasn’t going to demonstrations as much, and so with United in Anger there are demonstrations in the later part of the film that I didn’t attend. But they’re in the film because I felt these were important enough that they had to be there.

Schlemowitz: You were mentioning at the screening about where the footage came from – a collection that’s at the New York Public Library?

Hubbard: Yes, at the New York Public Library. What happened was, I was working at Anthology Film Archives. I worked there from 1992 to 1996. Originally I was hired to work on the exhibition side, but soon after that Anthology had one of its periodic financial crises. The archivist was laid off and many of the functions of that job were dumped in my lap. One of the reasons for this was that they were trying to do a computerized catalog and I was the only person working there who knew how to use a computer. [Laughs.] Yes, Jonas has, since that time, discovered the computer but back at that time he was still typing with two fingers on a manual typewriter. So I learned how to catalog film.

One day I answered the phone and it was a woman I knew named Lillian Jimenez. She was the head of Media Network at the time and they had gotten a small grant from the Estate Project of Artists with AIDS to try to figure out how to archive AIDS activist video. She thought, “We could just give it all to Anthology,” and I had to disabuse her of that notion. Anthology’s collection is almost exclusively film. It has a small video collection that’s mostly focused on art-video of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The AIDS activist videos just wouldn’t fit there. So they ended up hiring me to figure out where it should go. I started calling around to archives and talking to them about their facilities and collections, and whether they’d be interested in this footage. It was a huge amount of footage. James Wentzy alone had 750 hours of videotape. There was literally 2,000 hours of video and almost no one could deal with that.

At that point in time the Museum of Modern Art was buying two videos a year. UCLA could have dealt with it. But the New York Public Library was the only institution in the United States at that time that had an interest in AIDS-related material and the capacity for dealing with a huge amount of video, so it got housed in the Division of Archives and Manuscripts there. I should add that the original concept was that of Patrick Moore who was the head of the Estate Project. So then I was hired to call all these people up and say, “Hey, would you donate your footage to the New York Public Library?” It took a lot of convincing of people. What made it much easier was that they did not have to donate the copyright. They retained the copyright, they gave up the physical material, and the tapes were re-mastered to Betacam SP, the highest quality format available at the time. Since then it has all been digitized.

So there was all this footage available and even though I knew a lot of it I spent two years, three to five days a week, systematically looking at these videos. I ended up buying 75 hours of footage. They brought it to the lab where it was transferred to hard drive, and from that I cut it down to the 88 minutes of the film.

Schlemowitz: At what point did things coalesce between this footage existing, your connection with it, and the idea that you would be the person who would make this film?

Hubbard: It’s interesting, I don’t really remember. First, I should say that United in Anger grew out of my longtime work on the ACT UP Oral History Project. Sarah Schulman and I began that project in 2002. We do long format interviews of people who were and are in ACT UP, talking about their activism and their lives before, in, and, in some cases, after ACT UP. [For more information on the ACT UP Oral History Project, see www.actuporalhistory.org]. Before we started the project we met with Urvashi Vaid, who was then at the Ford Foundation. She’s someone I first met in 1980, when she was the head of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Sarah and I went to her to talk about getting a grant for the ACT UP Oral History Project. We did this whole presentation and at the end apparently I blurted out, “And I’m going to make a film.” I don’t remember saying that, but Urvashi remembers. So I guess I had the idea from the very beginning of the ACT UP Oral History Project.

We’ve done 187 interviews for the ACT UP Oral History Project, starting in 2002. The latest one was done in November 2015. I’d started editing United in Anger in 2008 and finished it in November of 2011. I think by 2011 we had recorded about 135 interviews. That was another 250 hours of footage that had to be edited down. What made that a lot easier was that the interviews were all transcribed. When my editor, Ali Cotterill said, “We need someone who can say something about affinity groups,” I could search in Word for “affinity groups” and find every person who had said something about this. That made the editing process a lot easier.

Going back to talking about the archival footage, during those two years that I spent at the NYPL looking at it I kept very specific notes on things that were in the footage, with timecode and a short description, and I put that into a database. That’s how I could make the decision about which tapes to buy. But also when it came to editing I could do searches on the database and find all the tapes that pertained to, say, the “Seize Control of the FDA” demonstration. I called it my paper edit; it was a very efficient way of organizing.

Schlemowitz: A very different process than a pair of film rewinds and a Moviscop.

Hubbard: Yes, completely. Because my editing process was experiential before that. What I would do was just assemble footage onto reels and look at it. Anything that didn’t work I’d immediately take out and it got shorter and shorter and shorter until I had this footage that was more or less in random order. At that point it became difficult, because that’s the point where you fall in love with your footage and you have to watch it over and over again until you’re sick of it! Then you can figure out what really works. The next step in my process was just to put it in an order: sometimes it was a very specific order, like “Oh, this shot would go great between this shot and that shot,” or sometimes it was just arbitrary and I would mix things up to get a different perspective on the footage. So I’d look at it and that would immediately help me find other shots that didn’t work. I think of editing on film as a sculptural process – it’s about paring away until you get to the real thing. It’s very different from editing on Final Cut which is the exact opposite most of the time. I think the paring away process is harder in Final Cut than it is in physical film.

Schlemowitz: How do you mean?

Hubbard: I tend to get lost in the shot: Where do I start this? Where do I end this? Somehow the process of seeing the physical film just lends itself to deciding this in a way that isn’t the case when looking at that long timeline on a computer screen. On the other hand, moving shots around is so much easier. I couldn’t go back to processing film again and editing on physical film. The chemistry is really bad for you, and now it just gives me headaches. So I’m trying to figure out a computerized version of it using After Effects.

Schlemowitz: Footsteps on the Ceiling (2013) is an example of this?

Hubbard: Yes, Footsteps on the Ceiling is an example, but actually all of that was done in Final Cut, so it is limited to the effects available in Final Cut. You can do a lot more with After Effects. But it’s harder to learn!

Published November 4, 2016

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joel Schlemowitz is an experimental filmmaker based in Brooklyn who works in 16mm film, shadowplay, and stereographic media. He has recently premiered his first feature film 78rpm, an experimental documentary about the gramophone. His short works have been shown at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, New York Film Festival, and Tribeca Film Festival and have received awards from the Chicago Underground Film Festival, The Dallas Video Festival, and elsewhere. Shows of installation artworks include Anthology Film Archives, and Microscope Gallery. He teaches experimental filmmaking at The New School and is Resident Film Programmer and Arcane Media Specialist at the Morbid Anatomy Museum. www.joelschlemowitz.com